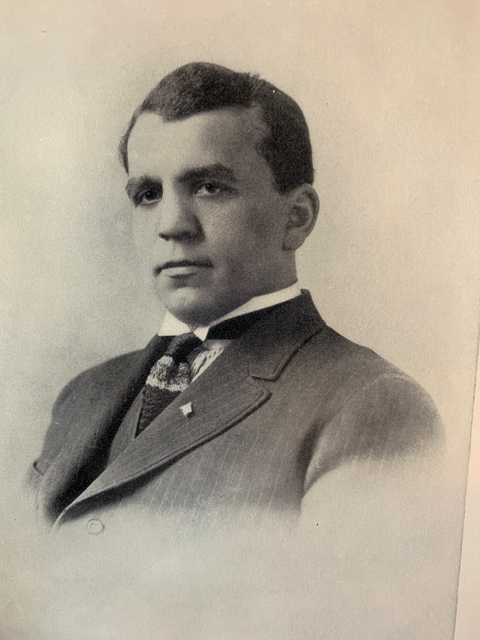

Sun Yat-sen (; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)[1][2] was the founding father of the Republic of China. The first provisional president of the Republic of China, Sun was a Chinese medical doctor, writer, philosopher, Georgist,[3][4]calligrapher,[5] and revolutionary. As the foremost pioneer and first leader of a Republican China, Sun is referred to as the "Father of the Nation" in the Republic of China (ROC) and the "forerunner of democratic revolution" in the People's Republic of China (PRC). Sun played an instrumental role in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty (the last imperial dynasty of China) during the years leading up to the Xinhai Revolution. He was appointed to serve as Provisional President of the Republic of China when it was founded in 1912. He later co-founded the Kuomintang(Nationalist Party of China), serving as its first leader.[6] Sun was a uniting figure in post-Imperial China, and he remains unique among 20th-century Chinese politicians for being widely revered amongst the people from both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

Although Sun is considered to be one of the greatest leaders of modern China, his political life was one of constant struggle and frequent exile. After the success of the revolution and the Han Chinese regaining power after 268 years of living under Manchurian rule (Qing dynasty), he quickly resigned from his post as President of the newly founded Republic of China to Yuan Shikai, and led successive revolutionary governments as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the nation. Sun did not live to see his party consolidate its power over the country during the Northern Expedition. His party, which formed a fragile alliance with the Chinese Communist Party, split into two factions after his death.

Sun's chief legacy resides in his developing of the political philosophy known as the Three Principles of the People: nationalism (Han Chinese nationalism: independence from imperialist domination – taking back power from the Manchurian Qing dynasty), "rights of the people," sometimes translated as "democracy,"[7] and the people's livelihood (just society).[8][9]

Birthplace and early life

Sun Yat-sen was born on 12 November 1866 to Sun Dacheng and Madame Yang.[2] His birthplace was the village of Cuiheng, Xiangshan County (now Zhongshan City), Guangdong.[2] He had a cultural background of Hakka (with roots in Zijin, Heyuan, Guangdong)[13] and Cantonese. His father owned very few lands and worked as a tailor in Macau, and as a journeyman and a porter.[14] After finishing primary education, he moved to Honolulu in the Kingdom of Hawaii, where he lived a comfortable life of modest wealth supported by his elder brother Sun Mei.[15][16][17][18]

Education years

At the age of 10, Sun Yat-sen began seeking schooling,[1] and he met childhood friend Lu Haodong.[1] By age 13 in 1878, after receiving a few years of local schooling, Sun went to live with his elder brother, Sun Mei(孫眉) in Honolulu.[1] Sun Mei financed Sun Yat-sen's education and would later be a major contributor for the overthrow of the Manchus.[15][16][17][18]

During his stay in Honolulu, Sun Yat-sen went to ʻIolani School where he studied English, British history, mathematics, science, and Christianity.[1] While he was originally unable to speak English, Sun Yat-sen quickly picked up the language and received a prize for academic achievement from King David Kalākaua before graduating in 1882.[19] He then attended Oahu College (now known as Punahou School) for one semester.[1][20] In 1883 he was sent home to China as his brother was becoming worried that Sun Yat-sen was beginning to embrace Christianity.[1]

When he returned to China in 1883 at age 17, Sun met up with his childhood friend Lu Haodong again at Beijidian (北極殿), a temple in Cuiheng Village.[1] They saw many villagers worshipping the Beiji (literally North Pole) Emperor-God in the temple, and were dissatisfied with their ancient healing methods.[1] They broke the statue, incurring the wrath of fellow villagers, and escaped to Hong Kong.[1][21][22] While in Hong Kong in 1883 he studied at the Diocesan Boys' School, and from 1884 to 1886 he was at The Government Central School.[23]

In 1886 Sun studied medicine at the Guangzhou Boji Hospital under the Christian missionary John G. Kerr.[1] Ultimately, he earned the license of Christian practice as a medical doctor from the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (the forerunner of The University of Hong Kong) in 1892.[1][12] Notably, of his class of 12 students, Sun was one of only two who graduated.[24][25][26]

Religious views and Christian baptism

In the early 1880s, Sun Mei sent his brother to ʻIolani School, which was under the supervision of British Anglicans and directed by an Anglican prelate named Alfred Willis. The language of instruction was English. Although Bishop Willis emphasized that no one was forced to accept Christianity, the students were required to attend chapel on Sunday. At Iolani School, young Sun Wen first came in contact with Christianity, and it made a deep impression on him. Schriffin writes that Christianity was to have a great influence on Sun's whole future political life.[27]

Sun was later baptized in Hong Kong (on 4 May 1884) by Rev. C. R. Hager[28][29][30] an American missionary of the Congregational Church of the United States (ABCFM) to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.[31][32] Sun attended To Tsai Church (道濟會堂), founded by the London Missionary Society in 1888,[33] while he studied Western Medicine in Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese. Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of the Christian church. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.[32]

Transformation into a revolutionary: Four Bandits

This is a photograph of Sun Yat-sen (seated, second from left) and his revolutionary friends, the Four Bandits, including Yeung Hok-ling(left), Chan Siu-bak (seated, second from right), Yau Lit (right), and Guan Jingliang (關景良) (standing) at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, circa 1888

During the Qing Dynasty rebellion around 1888, Sun was in Hong Kong with a group of revolutionary thinkers who were nicknamed the Four Bandits at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese.[34]Sun, who had grown increasingly frustrated by the conservative Qing government and its refusal to adopt knowledge from the more technologically advanced Western nations, quit his medical practice in order to devote his time to transforming China.

Furen and Revive China Society

In 1891, Sun met revolutionary friends in Hong Kong including Yeung Ku-wan who was the leader and founder of the Furen Literary Society.[35] The group was spreading the idea of overthrowing the Qing. In 1894, Sun wrote an 8,000 character petition to Qing Viceroy Li Hongzhang presenting his ideas for modernizing China.[36][37][38] He traveled to Tianjin to personally present the petition to Li but was not granted an audience.[39] After this experience, Sun turned irrevocably toward revolution. He left China for Hawaii and founded the Revive China Society, which was committed to revolutionizing China's prosperity. Members were drawn mainly from Chinese expatriates, especially the lower social classes. The same month in 1894 the Furen Literary Society was merged with the Hong Kong chapter of the Revive China Society.[35] Thereafter, Sun became the secretary of the newly merged Revive China society, which Yeung Ku-wan headed as president.[40] They disguised their activities in Hong Kong under the running of a business under the name "Kuen Hang Club"[41]:90(乾亨行).[42]

First Sino-Japanese War

In 1895, China suffered a serious defeat during the First Sino-Japanese War. There were two types of responses. One group of intellectuals contended that the Manchu Qing government could restore its legitimacy by successfully modernizing.[43] Stressing that overthrowing the Manchu would result in chaos and would lead to China being carved up by imperialists, intellectuals like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao supported responding with initiatives like the Hundred Days' Reform.[43] In another faction, Sun Yat-sen and others like Zou Rong wanted a revolution to replace the dynastic system with a modern nation-state in the form of a republic.[43] The Hundred Days' reform turned out to be a failure by 1898.[44]

From uprising to exile

First Guangzhou uprising

In the second year of the establishment of the Revive China society on 26 October 1895, the group planned and launched the First Guangzhou uprising against the Qing in Guangzhou.[37] Yeung Kui-wan directed the uprising starting from Hong Kong.[40]However, plans were leaked out and more than 70 members, including Lu Haodong, were captured by the Qing government. The uprising was a failure. Sun received financial support mostly from his brother who sold most of his 12,000 acres of ranch and cattle in Hawaii.[15] Additionally, members of his family and relatives of the Sun would take refuge at the home of his brother Sun Mei at Kamaole in Kula, Maui.[15][16][17][18][45]

Sun was in exile not only in Japan but also in Europe, the United States, and Canada. He raised money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. While the events leading up to it are unclear, in 1896 Sun Yat-sen was detained at the Chinese Legation in London, where the Chinese Imperial secret service planned to kill him.[53] He was released after 12 days through the efforts of James Cantlie, The Globe, The Times, and the Foreign Office, leaving Sun a hero in Britain.[54] James Cantlie, Sun's former teacher at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, maintained a lifelong friendship with Sun and would later write an early biography of Sun.[55]

Sun was in exile not only in Japan but also in Europe, the United States, and Canada. He raised money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. While the events leading up to it are unclear, in 1896 Sun Yat-sen was detained at the Chinese Legation in London, where the Chinese Imperial secret service planned to kill him.[53] He was released after 12 days through the efforts of James Cantlie, The Globe, The Times, and the Foreign Office, leaving Sun a hero in Britain.[54] James Cantlie, Sun's former teacher at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, maintained a lifelong friendship with Sun and would later write an early biography of Sun.[55]

Revolution

Tongmenghui

In 1904, Sun Yat-sen came about with the goal "to expel the Tatar barbarians (i.e. Manchu), to revive Zhonghua, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people" (驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權).[62] One of Sun's major legacies was the creation of his political philosophy of the Three Principles of the People. These Principles included the principle of nationalism (minzu, 民族), of democracy (minquan, 民權), and of welfare (minsheng, 民生).[62]

On 20 August 1905, Sun joined forces with revolutionary Chinese students studying in Tokyo, Japan to form the unified group Tongmenghui (United League), which sponsored uprisings in China.[62][63] By 1906 the number of Tongmenghui members reached 963 people.[62]

Zhennanguan uprising

On 1 December 1907, Sun led the Zhennanguan uprising against the Qing at Friendship Pass, which is the border between Guangxi and Vietnam.[69]The uprising failed after seven days of fighting.[69][70] In 1907 there were a total of four uprisings that failed including Huanggang uprising, Huizhou seven women lake uprising and Qinzhou uprising.[65] In 1908 two more uprisings failed one after another including Qin-lian uprising and Hekou uprising.[65]

1911 revolution

To sponsor more uprisings, Sun made a personal plea for financial aid at the Penang conference held on 13 November 1910 in Malaya.[72] The leaders launched a major drive for donations across the Malay Peninsula.[72] They raised HK$187,000.[72]

On 10 October 1911, a military uprising at Wuchang took place led again by Huang Xing. At the time, Sun had no direct involvement as he was still in exile. Huang was in charge of the revolution that ended over 2000 years of imperial rule in China. When Sun learned of the successful rebellion against the Qing emperor from press reports, he returned to China from the United States accompanied by his closest foreign advisor, the American, "General" Homer Lea. He met Lea in London, where he and Lea unsuccessfully tried to arrange British financing for the new Chinese republic. Sun and Lea then sailed for China, arriving there on 21 December 1911.[74]

The uprising expanded to the Xinhai Revolution also known as the "Chinese Revolution" to overthrow the last Emperor Puyi. After this event, 10 October became known as the commemoration of Double Ten Day.[75]

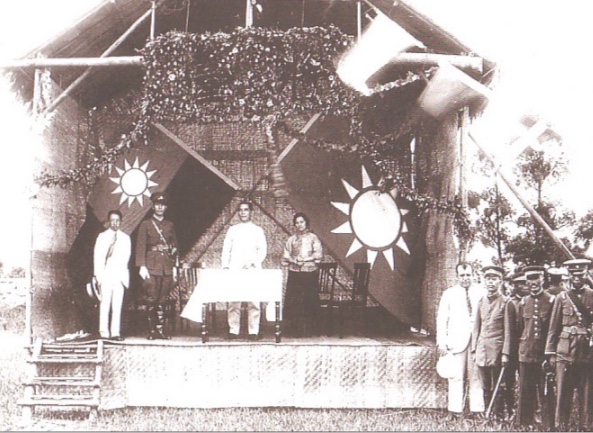

The Republic of China with multiple governments

On 29 December 1911, a meeting of representatives from provinces in Nanking (Nanjing) elected Sun Yat-sen as the "provisional president" (臨時大總統).[76] 1 January 1912 was set as the first day of the First Year of the Republic.[77] Li Yuanhongwas made provisional vice-president and Huang Xing became the minister of the army. The new Provisional Government of the Republic of China was created along with the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China. Sun is credited for the funding of the revolutions and for keeping the spirit of revolution alive, even after a series of failed uprisings. His successful merger of minor revolutionary groups to a single larger party provided a better base for all those who shared the same ideals. A number of things were introduced such as the republic calendar system and new fashion like Zhongshan suits.

Political chaos

In 1915 Yuan Shikai proclaimed the Empire of China (1915–1916) with himself as Emperor of China. Sun took part in the Anti-Monarchy war of the Constitutional Protection Movement, while also supporting bandit leaders like Bai Lang during the Bai Lang Rebellion. This marked the beginning of the Warlord Era. In 1915 Sun wrote to the Second International, a socialist-based organization in Paris, asking it to send a team of specialists to help China set up the world's first socialist republic.[82] At the time there were many theories and proposals of what China could be. In the political mess, both Sun Yat-sen and Xu Shichang were announced as President of the Republic of China.[83]

The path to the Northern Expedition: Guangzhou militarist government

China had become divided between different military leaders without a proper central government. Sun saw the danger of this and returned to China in 1917 to advocate Chinese reunification. In 1921 he started a self-proclaimed military government in Guangzhou and was elected Grand Marshal.[84] Between 1912 and 1927 three governments had been set up in South China: the Provisional government in Nanjing (1912), the Military government in Guangzhou (1921–1925), and the National government in Guangzhou and later Wuhan (1925–1927).[85] The southern separatist government in the South was established to rival the Beiyang government in the north.[84] Yuan Shikai had banned the KMT. The short-lived Chinese Revolutionary Party was a temporary replacement for the KMT. On 10 October 1919 Sun resurrected the KMT with the new name Chung-kuoKuomintang (simplified Chinese: 中国国民党; traditional Chinese: 中國國民黨; pinyin: Zhōngguó guómíndǎng), or the "Nationalist Party of China".[80]

KMT–CPC cooperation

By this time Sun had become convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period of political tutelage that would culminate in the transition to democracy. In order to hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active cooperation with the Communist Party of China (CPC). Sun and the Soviet Union's Adolph Joffe signed the Sun-Joffe Manifesto in January 1923.[86] Sun received help from the Comintern for his acceptance of communist members into his KMT. Revolutionary and socialist leader Vladimir Lenin praised Sun and the KMT for their ideology and principles. Lenin praised Sun and his attempts at social reformation, and also congratulated him for fighting foreign Imperialism.[87][88][89] Sun also returned the praise, calling him a "great man", and sent his congratulations on the revolution in Russia.[90]

With the Soviets' help, Sun was able to develop the military power needed for the Northern Expedition against the military at the north. He established the Whampoa Military Academy near Guangzhou with Chiang Kai-shek as the commandant of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA).[91] Other Whampoa leaders include Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin as political instructors. This full collaboration was called the First United Front.

Finance concerns

In 1924 Sun appointed his brother-in-law T. V. Soong to set up the first Chinese Central bank called the Canton Central Bank.[92] To establish national capitalism and a banking system was a major objective for the KMT.[93] However, Sun was not without some opposition as there was the Canton volunteers corps uprising against him.

Illness and death

For many years, it was popularly believed that Sun died of liver cancer. On 26 January 1925, Sun underwent an exploratory laparotomy at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) to investigate a long-term illness. This was performed by the head of the Department of Surgery, Adrian S. Taylor, who stated that the procedure "revealed extensive involvement of the liver by carcinoma" and that Sun only had about ten days to live. Sun was hospitalized and his condition was treated with radium. [99] Sun survived the initial ten-day period and on 18 February, against the advice of doctors, he was transferred to the KMT headquarters and treated with traditional Chinese medicine. This too was unsuccessful and he died on 12 March at the age of 58.[100] Contemporary reports in The New York Times,[100] Time,[101] and the Chinese newspaper Qun Qiang Bao all reported the cause of death as liver cancer, based on Taylor's observation.[102]

Following this, the body then was preserved in mineral oil[103] and taken to the Temple of Azure Clouds, a Buddhist shrine in the Western Hills a few miles outside of Beijing.[104][105] He also left a short political will (總理遺囑) penned by Wang Jingwei, which had a widespread influence in the subsequent development of the Republic of China and Taiwan.[106]

Cult of personality

A personality cult in the Republic of China was centered on Sun and his successor, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Chinese Muslim Generals and Imams participated in this cult of personality and one-party state, with Muslim General Ma Bufang making people bow to Sun's portrait and listen to the national anthem during a Tibetan and Mongol religious ceremony for the Qinghai Lake God.[109] Quotes from the Quran and Hadith were used among Hui Muslims to justify Chiang Kai-shek's rule over China.[110]

The Kuomintang's constitution designated Sun as party president. After his death, the Kuomintang opted to keep that language in its constitution to honor his memory forever. The party has since been headed by a director-general (1927–1975) and a chairman (since 1975), which discharge the functions of the president.

Family

Sun Yat-sen was born to Sun Dacheng (孫達成) and his wife, lady Yang (楊氏) on 12 November 1866.[113] At the time his father was age 53, while his mother was 38 years old. He had an older brother, Sun Dezhang (孫德彰), and an older sister, Sun Jinxing (孫金星), who died at the early age of 4. Another older brother, Sun Deyou (孫德祐), died at the age of 6. He also had an older sister, Sun Miaoqian (孫妙茜), and a younger sister, Sun Qiuqi (孫秋綺).[25]

At age 20, Sun had an arranged marriage with fellow villager Lu Muzhen. She bore a son, Sun Fo, and two daughters, Sun Jinyuan (孫金媛) and Sun Jinwan (孫金婉).[25] Sun Fo was the grandfather of Leland Sun, who spent 37 years working in Hollywood as an actor and stuntman.[114] Sun Yat-sen was also the godfather of Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, American author and poet who wrote under the name Cordwainer Smith.[115]

Sun's first concubine, the Hong Kong-born Chen Cuifen, lived in Taiping, Perak, Malaysia for 17 years. The couple adopted a local girl as their daughter. Cuifen subsequently relocated to China, where she passed away.[116]

On 25 October 1915 in Japan, Sun married Soong Ching-ling, one of the Soong sisters,[25][117] Soong Ching-Ling's father was the American-educated Methodist minister Charles Soong, who made a fortune in banking and in printing of Bibles. Although Charles Soong had been a personal friend of Sun's, he was enraged when Sun announced his intention to marry Ching-ling because while Sun was a Christian he kept two wives, Lu Muzhen and Kaoru Otsuki; Soong viewed Sun's actions as running directly against their shared religion.

On 25 October 1915 in Japan, Sun married Soong Ching-ling, one of the Soong sisters,[25][117] Soong Ching-Ling's father was the American-educated Methodist minister Charles Soong, who made a fortune in banking and in printing of Bibles. Although Charles Soong had been a personal friend of Sun's, he was enraged when Sun announced his intention to marry Ching-ling because while Sun was a Christian he kept two wives, Lu Muzhen and Kaoru Otsuki; Soong viewed Sun's actions as running directly against their shared religion.

Soong Ching-Ling's sister, Soong Mei-ling, later married Chiang Kai-shek.

References

- Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. 特別策劃 section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th-anniversary edition 民國之父.

- "Chronology of Dr. Sun Yat-sen". National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Karl Williams, "Sun Yat-sen And Georgism" https://www.prosper.org.au/about/geoists-in-history/sun-yat-sen-and-georgism/

- Archived version: https://web.archive.org/web/20180423084916/https://www.prosper.org.au/about/geoists-in-history/sun-yat-sen-and-georgism/

- Tingyou Chen, Chinese Calligraphy, Cambridge University Press (2011), p. 113

- Derek Benjamin Heater. [1987] (1987). Our world this century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-913324-6.

- "Three Principles of the People". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Trescott, Paul B. (2007). Jingji Xue: The History of the Introduction of Western Economic Ideas Into China, 1850–1950. Chinese University Press. pp. 46–48. 'The teachings of your single-taxer, Henry George, will be the basis of our program of reform.'

- Schoppa, Keith R. [2000] (2000). The Columbia guide to modern Chinese history. Columbia university press. ISBN 0-231-11276-9, ISBN 978-0-231-11276-5. p 282.

- Wang, Ermin (王爾敏). 思想創造時代:孫中山與中華民國. Showwe Information Co., Ltd. p. 274. ISBN 978-986-221-707-8.

- Wang, Shounan (王壽南) (2007). Sun Zhong-san. Commercial PressTaiwan. p. 23. ISBN 978-957-05-2156-6.

- 游梓翔 (2006). 領袖的聲音: 兩岸領導人政治語藝批評, 1906–2006. Wu-Nan Book Inc. p. 82. ISBN 978-957-11-4268-5.

- 门杰丹 (4 December 2003). 浓浓乡情系中原—访孙中山先生孙女孙穗芳博士 [Interview with Dr. Sun Yat-granddaughter of Dr. Sun Suifang]. www.chinanews.com (in Chinese). Retrieved 30 July 2012. Translate this Chinese article to English

- Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. 1998. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8047-4011-1.

- Kubota, Gary (20 August 2017). "Students from China study Sun Yat-sen on Maui". Star-Advertiser. Honolulu. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- KHON web staff (3 June 2013). "Chinese government officials attend Sun Mei statue unveiling on Maui". KHON2. Honolulu. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park". Hawaii Guide. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Sun Yet Sen Park". County of Maui. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (class of 1882)". ʻIolani School website. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- Brannon, John (16 August 2007). "Chinatown park, statue honor Sun Yat-sen". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 17 August 2007. Sun graduated from Iolani School in 1882, then attended Oahu College—now known as Punahou School—for one semester.

- 基督教與近代中國革命起源:以孫中山為例. Big5.chinanews.com:89. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September2011.

- 歷史與空間:基督教與近代中國革命的起源──以孫中山為例 – 香港文匯報. Paper.wenweipo.com. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Archived copy" 中山史蹟徑一日遊. Lcsd.gov.hk. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- HK university. [2002] (2002). Growing with Hong Kong: the University and its graduates: the first 90 years. ISBN 962-209-613-1, ISBN 978-962-209-613-4.

- Singtao daily. 28 February 2011. 特別策劃 section A10. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition.

- South China morning post. Birth of Sun heralds dawn of revolutionary era for China. 11 November 1999.

- [1], Sun Yat-sen and Christianity.

- "...At present there are some seven members in the interior belonging to our mission, and two here, one I baptized last Sabbath,a young man who is attending the Government Central School. We had a very pleasant communion service yesterday..." – Hager to Clark, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.17, p.3

- "...We had a pleasant communion yesterday and received one Chinaman into the church..." – Hager to Pond, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.18, p.3 postscript

- Rev. C. R. Hager, 'The First Citizen of the Chinese Republic', The Medical Missionary v.22 1913, p.184

- Bergère: 26

- Soong, (1997) p. 151-178

- 中西區區議會 [Central & Western District Council] (November 2006), 孫中山先生史蹟徑 [Dr Sun Yat-sen Historical Trail] (PDF), Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum (in Chinese and English), Hong Kong, China: Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum, p. 30, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2012, retrieved 15 September 2012

- Bard, Solomon. Voices from the past: Hong Kong, 1842–1918. [2002] (2002). HK university press. ISBN 962-209-574-7, ISBN 978-962-209-574-8. pg 183.

- Curthoys, Ann. Lake, Marilyn. [2005] (2005). Connected worlds: history in transnational perspective. ANU publishing. ISBN 1-920942-44-0, ISBN 978-1-920942-44-1. pg 101.

- Wei, Julie Lee. Myers Ramon Hawley. Gillin, Donald G. [1994] (1994). Prescriptions for saving China: selected writings of Sun Yat-sen. Hoover press. ISBN 0-8179-9281-2, ISBN 978-0-8179-9281-1.

- 王恆偉 (2006). #5 清 [Chapter 5. Qing dynasty]. 中國歷史講堂. 中華書局. p. 146. ISBN 962-8885-28-6.

- Bergère: 39–40

- Bergère: 40–41

- (Chinese) Yang, Bayun; Yang, Xing'an (November 2010). Yeung Ku-wan – A Biography Written by a Family Member. Bookoola. p. 17. ISBN 978-988-18-0416-7

- Faure, David (1997). Society. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622093935., founder Tse Tsan-tai's account

- 孫中山第一次辭讓總統並非給袁世凱 – 文匯資訊. Info.wenweipo.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September2011.

- Bevir, Mark. [2010] (2010). Encyclopedia of Political Theory. Sage publishing. ISBN 1-4129-5865-2, ISBN 978-1-4129-5865-3. pg 168.

- Lin, Xiaoqing Diana. [2006] (2006). Peking University: Chinese Scholarship And Intellectuals, 1898–1937. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-6322-2, ISBN 978-0-7914-6322-2. pg 27.

- Paul Wood (November–December 2011). "The Other Maui Sun". Wailuku, Hawaii: Maui Nō Ka ʻOi Magazine. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- "JapanFocus". Old.japanfocus.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Thornber, Karen Laura. [2009] (2009). Empire of Texts in Motion: Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Transculturations of Japanese Literature. Harvard university press. pg 404.

- Ocampo, Ambeth (2010). Looking Back 2. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing. pp. 8–11.

- Gao, James Zheng. [2009] (2009). Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949). Scarecrow press. ISBN 0-8108-4930-5, ISBN 978-0-8108-4930-3. Chronology section.

- Bergère: 86

- 劉崇稜 (2004). 日本近代文學精讀. p. 71. ISBN 978-957-11-3675-2.

- Frédéric, Louis. [2005] (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Harvard university press. ISBN 0-674-01753-6, ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. pg 651.

- "Sun Yat-sen | Chinese leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- Contrary to popular legends, Sun entered the Legation voluntarily, but was prevented from leaving. The Legation planned to execute him, before returning his body to Beijing for ritual beheading. Cantlie, his former teacher, was refused a writ of habeas corpus because of the Legation's diplomatic immunity, but he began a campaign through The Times. The Foreign Office persuaded the Legation to release Sun through diplomatic channels. Source: Wong, J.Y. (1986). The Origins of a Heroic Image: SunYat Sen in London, 1896–1987. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. as summarized in Clark, David J.; Gerald McCoy (2000). The Most Fundamental Legal Right: Habeas Corpus in the Commonwealth. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 162.

- Cantlie, James (1913). Sun Yat Sen and the Awakening of China. London: Jarrold & Sons.

- João de Pina-Cabral. [2002] (2002). Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao. Berg publishing. ISBN 0-8264-5749-5, ISBN 978-0-8264-5749-3. pg 209.

- England, Vaudine (17 September 2007). "Hong Kong rediscovers Sun Yat-sen". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- 孫中山思想 3學者演說精采. World journal. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Sun Yat-sen: Certification of Live Birth in Hawaii". San Francisco, CA, USA: Scribd. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Smyser, A.A. (2000). Sun Yat-sen's strong links to Hawaii. Honolulu Star Bulletin. "Sun renounced it in due course. It did, however, help him circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which became applicable when Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898."

- Department of Justice. Immigration and Naturalization Service. San Francisco District Office. "Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925" (PDF). Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004 ]. Washington, DC, USA: National Archives and Records Administration. pp. 92–152. Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925 at the National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original (PDF)on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2012. Note that one immigration official recorded that Sun Yat-sen was born in Kula, a district of Maui, Hawaii.

- 計秋楓, 朱慶葆. [2001] (2001). 中國近代史, Volume 1. Chinese university press. ISBN 962-201-987-0, ISBN 978-962-201-987-4. pg 468.

- "Internal Threats – The Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) – Imperial China – History – China – Asia". Countriesquest.com. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Streets of George Town, Penang. Areca Books. 2007. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-983-9886-00-9.

- Yan, Qinghuang. [2008] (2008). The Chinese in Southeast Asia and beyond: socioeconomic and political dimensions. World Scientific publishing. ISBN 981-279-047-0, ISBN 978-981-279-047-7. pg 182–187.

- "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall". Wanqingyuan.org.sg. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Eiji Murashima. "The Origins of Chinese Nationalism in Thailand" (PDF). Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies (Waseda University). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Eric Lim. "Soi Sun Yat Sen the legacy of a revolutionary". Tour Bangkok Legacies. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Khoo, Salma Nasution. [2008] (2008). Sun Yat Sen in Penang. Areca publishing. ISBN 983-42834-8-2, ISBN 978-983-42834-8-3.

- Tang Jiaxuan. [2011] (2011). Heavy Storm and Gentle Breeze: A Memoir of China's Diplomacy. HarperCollins publishing. ISBN 0-06-206725-7, ISBN 978-0-06-206725-8.

- Nanyang Zonghui bao. The Union Times paper. 11 November 1909 p2.

- Bergère: 188

- 王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 5 清. 中華書局. ISBN 962-8885-28-6. p 195-198.

- Bergère: 210

- Carol, Steven. [2009] (2009). Encyclopedia of Days: Start the Day with History. iUniverse publishing. ISBN 0-595-48236-8, ISBN 978-0-595-48236-8.

- Lane, Roger deWardt. [2008] (2008). Encyclopedia Small Silver Coins. ISBN 0-615-24479-3, ISBN 978-0-615-24479-2.

- Welland, Sasah Su-ling. [2007] (2007). A Thousand miles of dreams: The journeys of two Chinese sisters. Rowman littlefield publishing.ISBN 0-7425-5314-0, ISBN 978-0-7425-5314-9. pg 87.

- Fu, Zhengyuan. (1993). Autocratic tradition and Chinese politics(Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44228-1, ISBN 978-0-521-44228-2). pp. 153–154.

- Bergère: 226

- Ch'ien Tuan-sheng. The Government and Politics of China 1912–1949. Harvard University Press, 1950; rpr. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0551-8, ISBN 978-0-8047-0551-6. pp. 83–91.

- Ernest Young, "Politics in the Aftermath of Revolution," in John King Fairbank, ed., The Cambridge History of China: Republican China 1912–1949, Part 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1983; ISBN 0-521-23541-3, ISBN 978-0-521-23541-9), p. 228.

- South China morning post. Sun Yat-sen's durable and malleable legacy. 26 April 2011.

- South China morning post. 1913–1922. 9 November 2003.

- Bergère & Lloyd: 273

- Kirby, William C. [2000] (2000). State and economy in republican China: a handbook for scholars, volume 1. Harvard publishing. ISBN 0-674-00368-3, ISBN 978-0-674-00368-2. pg 59.

- Tung, William L. [1968] (1968). The political institutions of modern China. Springer publishing. ISBN 9789024705528. p 92. P106.

- Robert Payne (2008). Mao Tse-tung: Ruler of Red China. READ BOOKS. p. 22. ISBN 1-4437-2521-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 237. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov (1982). Great Soviet encyclopedia, Volume 25. Macmillan. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Bernice A Verbyla (2010). Aunt Mae's China. Xulon Press. p. 170. ISBN 1-60957-456-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Gao. James Zheng. [2009] (2009). Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949). Scarecrow press. ISBN 0-8108-4930-5, ISBN 978-0-8108-4930-3. pg 251.

- Spence, Jonathan D. [1990] (1990). The search for modern China. WW Norton & company publishing. ISBN 0-393-30780-8, ISBN 978-0-393-30780-1. Pg 345.

- Ji, Zhaojin. [2003] (2003). A history of modern Shanghai banking: the rise and decline of China's finance capitalism. M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 0-7656-1003-5, ISBN 978-0-7656-1003-4. pg 165.

- Ho, Virgil K.Y. [2005] (2005). Understanding Canton: Rethinking Popular Culture in the Republican Period. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928271-4

- Carroll, John Mark. Edge of Empires:Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong. Harvard university press. ISBN 0-674-01701-3

- Ma Yuxin [2010] (2010). Women journalists and feminism in China, 1898–1937. Cambria Press. ISBN 1-60497-660-8, ISBN 978-1-60497-660-1. p. 156.

- 马福祥,临夏回族自治州马福祥,马福祥介绍---走遍中国. www.elycn.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Calder, Kent; Ye, Min [2010] (2010). The Making of Northeast Asia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-6922-2, ISBN 978-0-8047-6922-8.

- Barth, Rolf F.; Chen, Jie (1 January 2016). "What did Sun Yat-sen really die of? A re-assessment of his illness and the cause of his death". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 35 (1): 81. doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0144-9. ISSN 1944-446X. PMC 5009495. PMID 27586157.

- "Dr. Sun Yat-sen Dies in Peking". The New York Times. 12 March 1925. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Lost Leader". Time. 23 March 1925. Retrieved 3 August 2008. A year ago his death was prematurely announced; but it was not until last January that he was taken to the Rockefeller Hospital at Peking and declared to be in the advanced stages of cancer of the liver.

- Sharman, L. (1968) [1934]. Sun Yat-sen: His life and times. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 305–306, 310.

- Bullock, M.B. (2011). The oil prince's legacy: Rockefeller philanthropy in China. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8047-7688-2.

- Leinwand, Gerald (9 September 2002). 1927: High Tide of the 1920's. Basic Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-56858-245-0. Retrieved 29 December2017.

- Dr Yat-Sen Sun at Find a Grave

- 國父遺囑 [Founding Father's Will]. Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- "Cancer Communications". Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- "Clinical record copies from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital decrypt the real cause of death of Sun Yat-sen". Nanfang Daily (in Chinese). 11 November 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 51. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 134; 375. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Rosecrance, Richard N. Stein, Arthur A. [2006] (2006). No more states?: globalization, national self-determination, and terrorism.Rowman & Littlefield publishing. ISBN 0-7425-3944-X, 9780742539440. pg 269.

- Nguyễn Văn Hồng. "Cao Đài Từ điển#Tam Thánh ký hòa ước". caodaism.org. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- 孫中山學術研究資訊網 – 國父的家世與求學 [Dr. Sun Yat-sen's family background and schooling]. [sun.yatsen.gov.tw/ sun.yatsen.gov.tw (in Chinese). 16 November 2005. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Sun Yat-sen's descendant wants to see unified China". News.xinhuanet.com. 11 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Tripping Cyborgs and Organ Farms: The Fictions of Cordwainer Smith | NeuroTribes". NeuroTribes. 21 September 2010. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- "Antong Cafe, The Oldest Coffee Mill in Malaysia". Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Isaac F. Marcosson, Turbulent Years (1938), p.249

- Guy, Nancy. [2005] (2005). Peking Opera and Politics in Taiwan. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02973-9. pg 67.

- "Sun Yet Sen Penang Base – News 17". Sunyatsenpenang.com. 19 November 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Sun Yat-sen's US birth certificate to be shown". Taipei Times. 2 October 2011. p. 3. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- +Indonesia/@3.5832583,98.689976,19.25z/data=!4m2!3m1!1s0x303131b3ac788419:0x5263731b3be58a57">"Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Queens Campus". www.youvisit.com. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "City to Dedicate Statue and Rename Park to Honor Dr. Sun Yat-Sen". The City and County of Honolulu. 12 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Sun Yat-sen". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "St. Mary's Square in San Francisco Chinatown – The largest chinatown outside of Asia". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne". www.cysm.org. Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "Char Asian-Pacific Study Room". Library.kcc.hawaii.edu. 23 June 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: Press Release Images: Spirit". Marsrover.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Opera Dr Sun Yat-sen to stage in Hong Kong". News.xinhuanet.com. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Gerard Raymond, "Between East and West: An Interview with David Henry Hwang" on slantmagazine.com, 28 October 2011

- "Commemoration of 1911 Revolution mounting in China". News.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Space: Above and Beyond s01e22 Episode Script SS". www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- 《斜路黃花》向革命者致意 (in Chinese). Takungpao.com. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- 元智大學管理學院 (in Chinese). Cm.yzu.edu.tw. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Kenneth Tan (3 October 2011). "Granddaughter of Sun Yat-Sen accuses China of distorting his legacy". Shanghaiist. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "Archived copy" 国父孙女轰中共扭曲三民主义愚民_多维新闻网 (in Chinese). China.dwnews.com. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- 人民网—孙中山遭辱骂 "台独"想搞"台湾国父". People's Daily. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Chiu Hei-yuan (5 October 2011). "History should be based on facts". Taipei Times. p. 8.

Further reading

- Soong, Irma Tam (1997). Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i. Hawai'i: The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 31.

- Shan, Patrick Fuliang (2018). Yuan Shikai: A Reappraisal, The University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 9780774837781.

- Sun Yat-sen's vision for China / Martin, Bernard, 1966.

- Sun Yat-sen, Yang Chu-yun, and the early revolutionary movement in China / Hsueh, Chun-tu

- Bergère, Marie-Claire (2000). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4011-9.

- Sun Yat-sen 1866–1925 / The Millennium Biographies / Hong Kong, 1999

- Sun Yat-sen and the origins of the Chinese revolution Schiffrin, Harold Z. /1968.

- Sun Yat-sen; his life and its meaning; a critical biography. Sharman, Lyon, / 1968, c. 1934

- Sun Yat Sen in Penang. Khoo Salma Nasution, Areca Books / 2008, c. 2010

- Sun Yat-sen and the Struggle for Modern China. Tjio, Kayloe. Marshall Cavendish / 2017.

- "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang memorial hall". Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Doctor Sun Yat Sen memorial hall". Retrieved 1 July 2005.

- "A detailed talk about Sun Zhongshan" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 5 April 2004. Retrieved 18 September 2005.

- "Toten Miyazaki bio".

- Pearl S. Buck, The Man Who Changed China: The Story of Sun Yat-sen (1953)

- Lawrence M. Kaplan, Homer Lea: American Soldier of Fortune (University Press of Kentucky, 2010).

External links

- ROC Government Biography (in English) (in Chinese)

- Sun Yat-sen in Hong Kong University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

- Contemporary views of Sun among overseas Chinese

- Yokohama Overseas Chinese School established by Dr. Sun Yat-sen

- National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall Official Website (in English) (in Chinese)

- Dr. Sun Yat Sen Middle School 131, New York City

- Dr. Sun Yat Sen Museum, Penang, Malaysia

- Homer Lea Research Center

- Was Yung Wing Dr. Sun's supporter? The Red Dragon scheme reveals the truth!

- Miyazaki Toten He devoted his life and energy to the Chinese people.

- MY GRANDFATHER, DR. SUN YAT-SEN – By Lily Sui-fong Sun

- 浓浓乡情系中原—访孙中山先生孙女孙穗芳博士 – 我的祖父是客家人. chinanews.com.cn. 2003-12-04.

- Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Foundation of Hawaii A virtual library on Dr. Sun in Hawaii including sources for six visits

- Who is Homer Lea? Sun's best friend. He trained Chinese soldiers and prepared the frame work for the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

- Works by Sun Yat-sen at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sun Yat-sen at Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about Sun Yat-sen in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byThe Xuantong Emperor(Puyi)as Emperor of the Qing dynasty | Head of state of Chinaas ProvisionalPresident of the Republic of China1912 | Succeeded byYuan Shih-kaias Provisional President of the Republic of China |

| Preceded byOffice created | Generalissimo of the Military Government of Nationalist China1917–1918 | Succeeded byGoverning Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China |

| Preceded byHimselfas Generalissimo of the Military Government of Nationalist China | Member of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China1918 | Succeeded byCen Chunxuanas Chairman of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China |

| Preceded byCen Chunxuanas Chairman of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China | Member of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China1920–1921 | Succeeded byHimselfas Extraordinary President of Nationalist China |

| Preceded byGeneralissimo of the Military Government of Nationalist China | Extraordinary President of Nationalist China1921–1922 | Succeeded byHimselfasGeneralissimo of the Nationalist China |

| Preceded byOffice created | Generalissimo of the National Government of Nationalist China1923–1925 | Succeeded byHu HanminActing |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded bySong Jiaorenas President of the Kuomintang | Premier of the Kuomintang1913–1914 | Succeeded byHimselfas Premier of the Chinese Revolutionary Party |

| Preceded byHimselfas Premier of the Chinese Revolutionary Party | Premier of the Kuomintang of China1919–1925 | Succeeded byZhang Renjieas Chairman |