Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin[b][c] (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili;[a] 18 December 1878 – 5 March 1953) was a Soviet revolutionary and politician of Georgian ethnicity. He ruled the Soviet Union from the mid–1920s until his death in 1953. Initially presiding over an oligarchic one-party system that governed by plurality, he became the de facto dictator of the Soviet state by the 1930s while holding the posts of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1922–1952) and Premier (1941–1953). A communist ideologically committed to the Leninist interpretation of Marxism, Stalin helped to formalise these ideas as Marxism–Leninism, while his own policies became known as Stalinism.

Born to a poor family in Gori, Russian Empire (now Georgia), Stalin joined the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party as a youth. He edited the party's newspaper, Pravda, and raised funds for Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction via robberies, kidnappings, and protection rackets. Repeatedly arrested, he underwent several internal exiles. After the Bolsheviks seized power during the 1917 October Revolution and created a one-party state under Lenin's newly renamed Communist Party, Stalin joined its governing Politburo. Serving in the Russian Civil War before overseeing the Soviet Union's establishment in 1922, Stalin assumed leadership over the country following Lenin's 1924 death. During Stalin's rule, "Socialism in One Country" became a central tenet of the party's dogma. Under the Five-Year Plans, the country underwent agricultural collectivisation and rapid industrialization, creating a centralized command economy. This led to significant disruptions in food production that contributed to the famine of 1932–33. To eradicate accused "enemies of the working class", Stalin instituted the "Great Purge", in which over a million were imprisoned and at least 700,000 executed between 1934 and 1939.

Stalin's government promoted Marxism–Leninism abroad through the Communist International and supported anti-fascist movements throughout Europe during the 1930s, particularly in the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, it signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, resulting in the Soviet invasion of Poland. Germany ended the pact by invading the Soviet Union in 1941. Despite initial setbacks, the Soviet Red Army repelled the German incursion and captured Berlin in 1945, ending World War II in Europe. The Soviets annexed the Baltic states and helped establish Soviet-aligned governments throughout Central and Eastern Europe, China and North Korea. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged from the war as the two world superpowers. Tensions arose between the Soviet-backed Eastern Bloc and U.S.-backed Western Bloc which became known as the Cold War. Stalin led his country through its post-war reconstruction, during which it developed a nuclear weapon in 1949. In these years, the country experienced another major famine and an anti-semitic campaign peaking in the Doctors' plot. Stalin died in 1953; he was eventually succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev, who denounced his predecessor and initiated a de-Stalinisation process throughout Soviet society.

Widely considered one of the 20th century's most significant figures, Stalin was the subject of a pervasive personality cult within the international Marxist–Leninist movement which revered him as a champion of the working class and world socialism. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Stalin has retained popularity in Russia and Georgia as a victorious wartime leader who established the Soviet Union as a major world power. Conversely, his totalitarian government has been widely condemned for overseeing mass repressions, ethnic cleansing, hundreds of thousands of executions, and famines which killed millions.

Early life

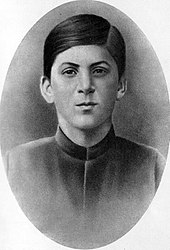

Childhood to young adulthood: 1878–1899

Stalin was born in the Georgian town of Gori[2] on 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878.[3][d] He was the son of Besarion "Beso" Jughashvili and Ekaterine "Keke" Geladze,[5] who had married in May 1872,[6] and had lost two sons in infancy prior to Stalin's birth.[7] They were ethnically Georgian, and Stalin grew up speaking the Georgian language.[8] Gori was then part of the Russian Empire, and was home to a population of 20,000, the majority of whom were Georgian but with Armenian, Russian, and Jewish minorities.[9] Stalin was baptised on 29 December.[10] He was nicknamed "Soso", a diminutive of "Ioseb".[11]

Besarion was a shoemaker and owned his own workshop;[12] it was initially a financial success, but later fell into decline.[13] The family found themselves living in poverty,[14] moving through nine different rented rooms in ten years.[15] Besarion became an alcoholic,[16]and drunkenly beat his wife and son.[17] To escape the abusive relationship, Keke took Stalin and moved into the house of a family friend, Fr. Christopher Charkviani.[18] She worked as a house cleaner and launderer for local families sympathetic to her plight.[19]Keke was determined to send her son to school, something that none of the family had previously achieved.[20] In late 1888, aged 10 Stalin enrolled at the Gori Church School. This was normally reserved for the children of clergy, although Charkviani ensured that the boy received a place.[21] Stalin excelled academically,[22] displaying talent in painting and drama classes,[23] writing his own poetry,[24] and singing as a choirboy.[25] He got into many fights,[26] and a childhood friend later noted that Stalin "was the best but also the naughtiest pupil" in the class.[27] Stalin faced several severe health problems; in 1884, he contracted smallpox and was left with facial pock scars.[28] Aged 12, he was seriously injured after being hit by a phaeton, which was the likely cause of a lifelong disability to his left arm.[29]

At his teachers' recommendation, Stalin proceeded to the Spiritual Seminary in Tiflis.[30] He enrolled at the school in August 1894,[31] enabled by a scholarship that allowed him to study at a reduced rate.[32] Here he joined 600 trainee priests who boarded at the seminary.[33] Stalin was again academically successful and gained high grades.[34] He continued writing poetry; five of his poems were published under the pseudonym of "Soselo" in Ilia Chavchavadze's newspaper Iveria ('Georgia').[35]Thematically, they dealt with topics like nature, land, and patriotism.[36]According to Stalin's biographer Simon Sebag Montefiore they became "minor Georgian classics",[37] and were included in various anthologies of Georgian poetry over the coming years.[37] As he grew older, Stalin lost interest in his studies; his grades dropped,[38] and he was repeatedly confined to a cell for his rebellious behaviour.[39] Teachers complained that he declared himself an atheist, chatted in class and refused to doff his hat to monks.[40]

Stalin joined a forbidden book club active at the school;[41] he was particularly influenced by Nikolay Chernyshevsky's 1863 pro-revolutionary novel What Is To Be Done?[42] Another influential text was Alexander Kazbegi's The Patricide, with Stalin adopting the nickname "Koba" from that of the book's bandit protagonist.[43] He also read Capital, the 1867 book by German sociological theorist Karl Marx.[44] Stalin devoted himself to Marx's socio-political theory, Marxism,[45] which was then on the rise in Georgia, one of various forms of socialism opposed to the empire's governing Tsarist authorities.[46] At night, he attended secret workers' meetings,[47] and was introduced to Silibistro "Silva" Jibladze, the Marxist founder of Mesame Dasi ('Third Group'), a Georgian socialist group.[48]Stalin left the seminary in April 1899; he never returned,[49] although the school encouraged him to come back.[50]

Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party: 1899–1904

In October 1899, Stalin began work as a meteorologist at a Tiflis observatory.[51] He attracted a group of supporters through his classes in socialist theory,[52] and co-organised a secret workers' mass meeting for May Day 1900,[53] at which he successfully encouraged many of the men to take strike action.[54] By this point, the empire's secret police—the Okhrana—were aware of Stalin's activities within Tiflis' revolutionary milieu.[54]They attempted to arrest him in March 1901, but he escaped and went into hiding,[55] living off the donations of friends and sympathisers.[56] Remaining underground, he helped plan a demonstration for May Day 1901, in which 3,000 marchers clashed with the authorities.[57] He continued to evade arrest by using aliases and sleeping in different apartments.[58] In November 1901, he was elected to the Tiflis Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), a Marxist party founded in 1898.[59]

That month, Stalin travelled to the port city of Batumi.[60] His militant rhetoric proved divisive among the city's Marxists, some of whom suspected that he might be an agent provocateur working for the government.[61] He found employment at the Rothschild refinery storehouse, where he co-organised two workers' strikes.[62] After several strike leaders were arrested, he co-organised a mass public demonstration that led to the storming of the prison; troops fired upon the demonstrators, 13 of whom were killed.[63] Stalin organised a second mass demonstration on the day of their funeral,[64] before being arrested in April 1902.[65] He was initially held at Batumi Prison,[66] and later moved to the more secure Kutaisi Prison.[67] In mid-1903, Stalin was sentenced to three years of exile in eastern Siberia.[68]

Stalin left Batumi in October, arriving at the small Siberian town of Novaya Uda in late November.[69] There, he lived in a two-room peasant's house, sleeping in the building's larder.[70] He made two escape attempts; on the first he made it to Balagansk before returning due to frostbite.[71] His second attempt was successful and he made it to Tiflis.[72] There, he co-edited a Georgian Marxist newspaper, Proletariatis Brdzola ("Proletarian Struggle"), with Philip Makharadze.[73] He called for the Georgian Marxist movement to split off from its Russian counterpart, resulting in several RSDLP members accusing him of holding views contrary to the ethos of Marxist internationalism and calling for his expulsion from the party; he soon recanted his opinions.[74] During his exile, the RSDLP had split between Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks and Julius Martov's Mensheviks.[75]Stalin detested many of the Mensheviks in Georgia and aligned himself with the Bolsheviks.[76] Although Stalin established a Bolshevik stronghold in the mining town of Chiatura,[77] Bolshevism remained a minority force in the Menshevik-dominated Georgian revolutionary scene.[78]

The Revolution of 1905 and its aftermath: 1905–1912

In January 1905, government troops massacred protesters in Saint Petersburg.[79] Unrest soon spread across the Russian Empire in what came to be known as the Revolution of 1905.[79] Georgia was one of the regions particularly affected.[80] Stalin was in Baku in February when ethnic violence broke out between Armenians and Azeris; at least 2,000 were killed.[81] He publicly lambasted the "pogroms against Jews and Armenians" as being part of Tsar Nicholas II's attempts to "buttress his despicable throne".[82] Stalin formed a Bolshevik Battle Squad which he used to try and keep Baku's warring ethnic factions apart; he also used the unrest as a cover for stealing printing equipment.[82] Amid the growing violence throughout Georgia he formed further Battle Squads, with the Mensheviks doing the same.[83] Stalin's Squads disarmed local police and troops,[84] raided government arsenals,[85] and raised funds through protection rackets on large local businesses and mines.[86] They launched attacks on the government's Cossack troops and pro-Tsarist Black Hundreds,[87] co-ordinating some of their operations with the Menshevik militia.[88]

Stalin first met Vladimir Lenin (pictured) at a 1905 conference in Tampere. Lenin became "Stalin's indispensable mentor".[89]

Stalin first met Vladimir Lenin (pictured) at a 1905 conference in Tampere. Lenin became "Stalin's indispensable mentor".[89]

In November 1905, the Georgian Bolsheviks elected Stalin as one of their delegates to a Bolshevik conference in Saint Petersburg.[90] On arrival, he met Lenin's wife Nadezhda Krupskaya, who informed him that the venue had been moved to Tampere in the Grand Duchy of Finland.[91] At the conference Stalin met Lenin for the first time.[92] Although Stalin held Lenin in deep respect, he was vocal in his disagreement with Lenin's view that the Bolsheviks should field candidates for the forthcoming election to the State Duma; Stalin saw the parliamentary process as a waste of time.[93] In April 1906, Stalin attended the RSDLP Fourth Congress in Stockholm; this was his first trip outside the Russian Empire.[94] At the conference, the RSDLP—then led by its Menshevik majority—agreed that it would not raise funds using armed robbery.[95] Lenin and Stalin disagreed with this decision,[96] and later privately discussed how they could continue the robberies for the Bolshevik cause.[97]

Stalin married Kato Svanidze in a church ceremony at Senaki in July 1906.[98] In March 1907 she bore a son, Yakov.[99] By that year—according to the historian Robert Service—Stalin had established himself as "Georgia's leading Bolshevik".[100] He attended the Fifth RSDLP Congress, held in London in May–June 1907.[101] After returning to Tiflis, Stalin organized the robbing of a large delivery of money to the Imperial Bank in June 1907. His gang ambushed the armed convoy in Yerevan Square with gunfire and home-made bombs. Around 40 people were killed, but all of his gang escaped alive.[102] After the heist, Stalin settled in Baku with his wife and son.[103] There, Mensheviks confronted Stalin about the robbery and voted to expel him from the RSDLP, but he took no notice of them.[104]

In Baku, Stalin secured Bolshevik domination of the local RSDLP branch,[105] and edited two Bolshevik newspapers, Bakinsky Proletary and Gudok ("Whistle").[106] In August 1907, he attended the Seventh Congress of the Second International—an international socialist organisation—in Stuttgart, Germany.[107] In November 1907, his wife died of typhus,[108] and he left his son with her family in Tiflis.[109] In Baku he had reassembled his gang, the Outfit,[110] which continued to attack Black Hundreds and raised finances by running protection rackets, counterfeiting currency, and carrying out robberies.[111] They also kidnapped the children of several wealthy figures to extract ransom money.[112] In early 1908, he travelled to the Swiss city of Geneva to meet with Lenin and the prominent Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov, although the latter exasperated him.[113]

In March 1908, Stalin was arrested and interned in Bailov Prison.[114] There, he led the imprisoned Bolsheviks, organised discussion groups, and ordered the killing of suspected informants.[115] He was eventually sentenced to two years exile in the village of Solvychegodsk, Vologda Province, arriving there in February 1909.[116] In June, he escaped the village and made it to Kotlas disguised as a woman and from there to Saint Petersburg.[117] In March 1910, he was arrested again, and sent back to Solvychegodsk.[118] There he had affairs with at least two women; his landlady, Maria Kuzakova, later gave birth to his second son, Konstantin.[119] In June 1911, Stalin was given permission to move to Vologda, where he stayed for two months,[120] having a relationship with Pelageya Onufrieva.[121] He escaped to Saint Petersburg,[122] where he was arrested in September 1911, and sentenced to a further three-year exile in Vologda.[123]

Rise to the Central Committee and editorship of Pravda: 1912–1917

While Stalin was in exile, the first Bolshevik Central Committee had been elected at the Prague Conference, after which Lenin and Grigory Zinoviev invited Stalin to join it. Still in Vologda, Stalin agreed, remaining a Central Committee member for the rest of his life.[124] Lenin believed that Stalin, as a Georgian, would help secure support for the Bolsheviks from the Empire's minority ethnicities.[125] In February 1912, Stalin again escaped to Saint Petersburg,[126]tasked with converting the Bolshevik weekly newspaper, Zvezda ("Star") into a daily, Pravda ("Truth").[127] The new newspaper was launched in April 1912,[128] although Stalin's role as editor was kept secret.[128]

In May 1912, he was arrested again and imprisoned in the Shpalerhy Prison, before being sentenced to three years exile in Siberia.[129] In July, he arrived at the Siberian village of Narym,[130] where he shared a room with fellow Bolshevik Yakov Sverdlov.[131] After two months, Stalin and Sverdlov escaped back to Saint Petersburg.[132] During a brief period back in Tiflis, Stalin and the Outfit planned the ambush of a mail coach, during which most of the group—although not Stalin—were apprehended by the authorities.[133] Stalin returned to Saint Petersburg, where he continued editing and writing articles for Pravda.[134]

After the October 1912 Duma elections resulted in six Bolsheviks and six Mensheviks being elected, Stalin wrote articles calling for reconciliation between the two Marxist factions, for which he was criticised by Lenin.[135] In late 1912, he twice crossed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire to visit Lenin in Kraków,[136]eventually bowing to Lenin's opposition to reunification with the Mensheviks.[137] In January 1913 Stalin travelled to Vienna,[138] there focusing on the 'national question' of how the Bolsheviks should deal with the Russian Empire's national and ethnic minorities.[139] Lenin wanted to attract these groups to the Bolshevik cause by offering them the right of secession from the Russian state, but at the same time hoped they would remain part of a future Bolshevik-governed Russia.[140] Stalin's finished article was titled Marxism and the National Question;[141] Lenin was very happy with it.[142] According to Montefiore, this was "Stalin's most famous work".[140] The article was published under the pseudonym of "K. Stalin",[142] a name he had been using since 1912.[143] Derived from the Russian word for steel (stal),[144] this has been translated as "Man of Steel";[145]Stalin may have intended it to imitate Lenin's pseudonym.[146] Stalin retained this name for the rest of his life, possibly because it had been used on the article which established his reputation among the Bolsheviks.[147]

In February 1913, Stalin was arrested while back in Saint Petersburg.[148]He was sentenced to four years exile in Turukhansk, a remote part of Siberia from which escape was particularly difficult.[149] In August, he arrived in the village of Monastyrskoe, although after four weeks was relocated to the hamlet of Kostino.[150] In March 1914, concerned over a potential escape attempt, the authorities moved Stalin to the hamlet of Kureika on the edge of the Arctic Circle.[151] In the hamlet, Stalin had a relationship with Lidia Pereprygia, who was thirteen at the time and thus a year under the legal age of consent in Tsarist Russia.[152] In or about December 1914, Pereprygia gave birth to Stalin's child, although the infant soon died.[153] She gave birth to another of his children, Alexander, circa April 1917.[154] In Kureika, Stalin lived closely with the indigenous Tunguses and Ostyak,[155] and spent much of his time fishing.[156]

The Russian Revolution: 1917

While Stalin was in exile, Russia entered the First World War, and in October 1916 Stalin and other exiled Bolsheviks were conscripted into the Russian Army, leaving for Monastyrskoe.[157] They arrived in Krasnoyarskin February 1917,[158] where a medical examiner ruled Stalin unfit for military service due to his crippled arm.[159] Stalin was required to serve four more months on his exile, and he successfully requested that he serve it in nearby Achinsk.[160] Stalin was in the city when the February Revolution took place; uprisings broke out in Petrograd—as Saint Petersburg had been renamed—and Tsar Nicholas II abdicated to escape being violently overthrown. The Russian Empire became a de facto republic, headed by a Provisional Government dominated by liberals.[161]In a celebratory mood, Stalin travelled by train to Petrograd in March.[162]There, Stalin and fellow Bolshevik Lev Kamenev assumed control of Pravda,[163] and Stalin was appointed the Bolshevik representative to the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, an influential council of the city's workers.[164] In April, Stalin came third in the Bolshevik elections for the party's Central Committee; Lenin came first and Zinoviev came second.[165] This reflected his senior standing in the party at the time.[166]

The existing government of landlords and capitalists must be replaced by a new government, a government of workers and peasants.The existing pseudo-government which was not elected by the people and which is not accountable to the people must be replaced by a government recognised by the people, elected by representatives of the workers, soldiers and peasants and held accountable to their representatives.

— Stalin's editorial in Pravda, October 1917[167]

Stalin helped organise the July Days uprising, an armed display of strength by Bolshevik supporters.[168] After the demonstration was suppressed, the Provisional Government initiated a crackdown on the Bolsheviks, raiding Pravda.[19] During this raid, Stalin smuggled Lenin out of the newspaper's office and took charge of the Bolshevik leader's safety, moving him between Petrograd safe houses before smuggling him to Razliv.[169] In Lenin's absence, Stalin continued editing Pravda and served as acting leader of the Bolsheviks, overseeing the party's Sixth Congress, which was held covertly.[170] Lenin began calling for the Bolsheviks to seize power by toppling the Provisional Government in a coup d'état. Stalin and fellow senior Bolshevik Leon Trotsky both endorsed Lenin's plan of action, but it was initially opposed by Kamenev and other party members.[171] Lenin returned to Petrograd and secured a majority in favour of a coup at a meeting of the Central Committee on 10 October.[172]

On 24 October, police raided the Bolshevik newspaper offices, smashing machinery and presses; Stalin salvaged some of this equipment to continue his activities.[173] In the early hours of 25 October, Stalin joined Lenin in a Central Committee meeting in the Smolny Institute, from where the Bolshevik coup—the October Revolution—was directed.[174] Bolshevik militia seized Petrograd's electric power station, main post office, state bank, telephone exchange, and several bridges.[175] A Bolshevik-controlled ship, the Aurora, opened fire on the Winter Palace; the Provisional Government's assembled delegates surrendered and were arrested by the Bolsheviks.[176] Although he had been tasked with briefing the Bolshevik delegates of the Second Congress of Soviets about the developing situation, Stalin's role in the coup had not been publicly visible.[177] Trotsky and other later Bolshevik opponents of Stalin used this as evidence that his role in the coup had been insignificant, although later historians reject this.[178] According to the historian Oleg Khlevniuk, Stalin "filled an important role [in the October Revolution]... as a senior Bolshevik, member of the party's Central Committee, and editor of its main newspaper";[179] the historian Stephen Kotkin similarly noted that Stalin had been "in the thick of events" in the build-up to the coup.[180]

In Lenin's government

Consolidating power: 1917–1918

On 26 October, Lenin declared himself Chairman of a new government, the Council of People's Commissars ("Sovnarkom").[181] Stalin backed Lenin's decision not to form a coalition with the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionary Party, although they did form a coalition government with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries.[182] Stalin became part of an informal foursome leading the government, alongside Lenin, Trotsky, and Sverdlov;[183] of these, Sverdlov was regularly absent, and died in March 1919.[184]Stalin's office was based near to Lenin's in the Smolny Institute,[185] and he and Trotsky were the only individuals allowed access to Lenin's study without an appointment.[186] Although not so publicly well known as Lenin or Trotsky,[187] Stalin's importance among the Bolsheviks grew.[188]He co-signed Lenin's decrees shutting down hostile newspapers,[189] and with Sverdlov chaired the sessions of the committee drafting a constitution for the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[190]He strongly supported Lenin's formation of the Cheka security service and the subsequent Red Terror that it initiated; noting that state violence had proved an effective tool for capitalist powers, he believed that it would prove the same for the Soviet government.[191] Unlike senior Bolsheviks like Kamenev and Nikolai Bukharin, Stalin never expressed concern about the rapid growth and expansion of the Cheka and Terror.[191]

Having dropped his editorship of Pravda,[192] Stalin was appointed the People's Commissar for Nationalities.[193] He took Nadezhda Alliluyeva as his secretary,[194]and at some point married her, although the wedding date is unknown.[195] In November 1917, he signed the Decree on Nationality, according ethnic and national minorities living in Russia the right of secession and self-determination.[196] The decree's purpose was primarily strategic; the Bolsheviks wanted to gain favour among ethnic minorities but hoped that the latter would not actually desire independence.[197] That month, he travelled to Helsinki to talk with the Finnish Social-Democrats, granting Finland's request for independence in December.[197] His department allocated funds for the establishment of presses and schools in the languages of various ethnic minorities.[198] Socialist Revolutionaries accused Stalin's talk of federalism and national self-determination as a front for Sovnarkom's centralising and imperialist policies.[190]

Due to the ongoing First World War, in which Russia was fighting the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary, Lenin's government relocated from Petrograd to Moscow in March 1918. There, they based themselves in the Kremlin; it was here that Stalin, Trotsky, Sverdlov, and Lenin lived.[199] Stalin supported Lenin's desire to sign an armistice with the Central Powers regardless of the cost in territory.[200] Stalin thought it necessary because—unlike Lenin—he was unconvinced that Europe was on the verge of proletarian revolution.[201] Lenin eventually convinced the other senior Bolsheviks of his viewpoint, resulting in the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918.[202] The treaty gave vast areas of land and resources to the Central Powers and angered many in Russia; the Left Socialist Revolutionaries withdrew from the coalition government over the issue.[203] The governing RSDLP party was soon renamed, becoming the Russian Communist Party.[204]

Military Command: 1918–1921

After the Bolsheviks seized power, both right and left-wing armies rallied against them, generating the Russian Civil War.[205] To secure access to the dwindling food supply, in May 1918 Sovnarkom sent Stalin to Tsaritsynto take charge of food procurement in southern Russia.[206] Eager to prove himself as a commander,[207] once there he took control of regional military operations.[208] He befriended two military figures, Kliment Voroshilov and Semyon Budyonny, who would form the nucleus of his military and political support base.[209] Believing that victory was assured by numerical superiority, he sent large numbers of Red Army troops into battle against the region's anti-Bolshevik White armies, resulting in heavy losses; Lenin was concerned by this costly tactic.[210] In Tsaritsyn, Stalin commanded the local Cheka branch to execute suspected counter-revolutionaries, sometimes without trial,[211] and—in contravention of government orders—purged the military and food collection agencies of middle-class specialists, some of whom he also executed.[212] His use of state violence and terror was at a greater scale than most Bolshevik leaders approved of;[213] for instance, he ordered several villages to be torched to ensure compliance with his food procurement program.[214]

Joseph Stalin, Lenin, and Mikhail Kalinin meeting in 1919. All three of them were "Old Bolsheviks"—members of the Bolshevik party before the October Revolution.

Joseph Stalin, Lenin, and Mikhail Kalinin meeting in 1919. All three of them were "Old Bolsheviks"—members of the Bolshevik party before the October Revolution.

In December 1918, Stalin was sent to Permto lead an inquiry into how Alexander Kolchak's White forces had been able to decimate Red troops based there.[215] He returned to Moscow between January and March 1919,[216] before being assigned to the Western Front at Petrograd.[217] When the Red Third Regiment defected, he ordered the public execution of captured defectors.[216] In September he was returned to the Southern Front.[216] During the war, he proved his worth to the Central Committee, displaying decisiveness, determination, and a willingness to take on responsibility in conflict situations.[207] At the same time, he disregarded orders and repeatedly threatened to resign when affronted.[218] In November 1919, the government awarded him the Order of the Red Banner for his wartime service.[219]

The Bolsheviks had won the civil war by late 1919.[220] Sovnarkom turned its attention to spreading proletarian revolution abroad, to this end forming the Communist International in March 1919; Stalin attended its inaugural ceremony.[221] Although Stalin did not share Lenin's belief that Europe's proletariat were on the verge of revolution, he acknowledged that as long as it stood alone, Soviet Russia remained vulnerable.[222] In December 1918, he drew up decrees recognising Marxist-governed Soviet republics in Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia;[223] during the civil war these Marxist governments were overthrown and the Baltic countries became fully independent of Russia, an act Stalin regarded as illegitimate.[224] In February 1920, he was appointed to head the Workers' and Peasants' Inspectorate;[225] that same month he was also transferred to the Caucasian Front.[226]

Following earlier clashes between Polish and Russian troops, the Polish–Soviet War broke out in early 1920, with the Poles invading Ukraine and taking Kiev.[227] Stalin was moved to Ukraine, on the Southwest Front.[228]The Red Army forced the Polish troops back into Poland.[229] Lenin believed that the Polish proletariat would rise up to support the Russians against Józef Piłsudski's Polish government. Stalin had cautioned against this; he believed that nationalism would lead the Polish working-classes to support their government's war effort. He also believed that the Red Army was ill-prepared to conduct an offensive war and that it would give White Armies a chance to resurface in Crimea, potentially reigniting the civil war.[230] Stalin lost the argument, after which he accepted Lenin's decision and supported it.[226] Along the Southwest Front, he became determined to conquer Lwów; in focusing on this goal he disobeyed orders to transfer his troops to assist Mikhail Tukhachevsky's forces.[231] In August, the Poles repulsed the Russian advance and Stalin returned to Moscow.[232] A Polish-Soviet peace treaty was signed; Stalin saw this as a failure for which he blamed Trotsky.[233] In turn, Trotsky accused Stalin of "strategic mistakes" in his handling of the war at the Ninth Bolshevik Conference.[234] Stalin felt resentful and under-appreciated; in September he demanded demission from the military, which was granted.[235]

Lenin's final years: 1921–1923

The Soviet government sought to bring neighbouring states under its domination; in February 1921 it invaded the Menshevik-governed Georgia,[236] while in April 1921, Stalin ordered the Red Army into Turkestanto reassert Russian state control.[237] As People's Commissar for Nationalities, Stalin believed that each national and ethnic group should have the right to self-expression,[238] facilitated through "autonomous republics" within the Russian state in which they could oversee various regional affairs.[239] In taking this view, some Marxists accused him of bending too much to bourgeois nationalism, while others accused him of remaining too Russocentric by seeking to retain these nations within the Russian state.[238]

Stalin's native Caucasus posed a particular problem due to its highly multi-ethnic mix.[240] Stalin opposed the idea of separate Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijani autonomous republics, arguing that these would likely oppress ethnic minorities within their respective territories; instead he called for a Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.[241] The Georgian Communist Party opposed the idea, resulting in the Georgian Affair.[242] In mid-1921, Stalin returned to the southern Caucasus, there calling on Georgian Communists to avoid the chauvinistic Georgian nationalism which marginalised the Abkhazian, Ossetian, and Adjarian minorities in Georgia.[243] On this trip, Stalin met with his son Yakov, and brought him back to Moscow;[244] Nadya had given birth to another of Stalin's sons, Vasily, in March 1921.[244]

After the civil war, workers' strikes and peasant uprisings broke out across Russia, largely in opposition to Sovnarkom's food requisitioning project; as an antidote, Lenin introduced market-oriented reforms: the New Economic Policy (NEP).[245] There was also internal turmoil in the Communist Party, as Trotsky led a faction calling for the abolition of trade unions; Lenin opposed this and Stalin helped rally opposition to Trotsky's position.[246]Stalin also agreed to supervise the Department of Agitation and Propaganda in the Central Committee Secretariat.[247] At the 11th Party Congress in 1922, Lenin nominated Stalin as the party's new General Secretary. Although concerns were expressed that adopting this new post on top of his others would overstretch his workload and give him too much power, Stalin was appointed to the position.[248] For Lenin, it was advantageous to have a key ally in this crucial post.[249]

Stalin is too crude, and this defect which is entirely acceptable in our milieu and in relationships among us as communists, becomes unacceptable in the position of General Secretary. I therefore propose to comrades that they should devise a means of removing him from this job and should appoint to this job someone else who is distinguished from comrade Stalin in all other respects only by the single superior aspect that he should be more tolerant, more polite and more attentive towards comrades, less capricious, etc.

— Lenin's Testament, 4 January 1923;[250] this was possibly composed by Krupskaya rather than Lenin himself.[251]

In May 1922, a massive stroke left Lenin partially paralysed.[252] Residing at his Gorki dacha, Lenin's main connection to Sovnarkom was through Stalin, who was a regular visitor.[253] Lenin twice asked Stalin to procure poison so that he could commit suicide, but Stalin never did so.[254]Despite this comradeship, Lenin disliked what he referred to as Stalin's "Asiatic" manner, and told his sister Maria that Stalin was "not intelligent".[255] Lenin and Stalin argued on the issue of foreign trade; Lenin believed that the Soviet state should have a monopoly on foreign trade, but Stalin supported Grigori Sokolnikov's view that doing so was impractical at that stage.[256] Another disagreement came over the Georgian Affair, with Lenin backing the Georgian Central Committee's desire for a Georgian Soviet Republic over Stalin's idea of a Transcaucasian one.[257]

They also disagreed on the nature of the Soviet state. Lenin called for the country to be renamed the "Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia", reflecting his desire for expansion across the two continents. Stalin believed this would encourage independence sentiment among non-Russians, instead arguing that ethnic minorities would be content as "autonomous republics" within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[258] Lenin accused Stalin of "Great Russian chauvinism"; Stalin accused Lenin of "national liberalism".[259] A compromise was reached, in which the country would be renamed the "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics" (USSR).[260] The USSR's formation was ratified in December 1922; although officially a federal system, all major decisions were taken by the governing Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Moscow.[261]

Their differences also became personal; Lenin was particularly angered when Stalin was rude to his wife Krupskaya during a telephone conversation.[262] In the final years of his life, Krupskaya provided governing figures with Lenin's Testament, a series of increasingly disparaging notes about Stalin. These criticized Stalin's rude manners and excessive power, suggesting that Stalin should be removed from the position of General Secretary.[263] Some historians have questioned whether Lenin ever produced these, suggesting instead that they may have been written by Krupskaya, who had personal differences with Stalin;[251] Stalin, however, never publicly voiced concerns about their authenticity.[264]

Rise to power

Succeeding Lenin: 1924–1927

Lenin died in January 1924.[265] Stalin took charge of the funeral and was one of its pallbearers; against the wishes of Lenin's widow, the Politburo embalmed his corpse and placed it within a mausoleum in Moscow's Red Square.[266] It was incorporated into a growing personality cult devoted to Lenin, with Petrograd being renamed "Leningrad" that year.[267]To bolster his image as a devoted Leninist, Stalin gave nine lectures at Sverdlov University on the "Foundations of Leninism", later published in book form.[268] At the following 13th Party Congress, "Lenin's Testament" was read to senior figures. Embarrassed by its contents, Stalin offered his resignation as General Secretary; this act of humility saved him and he was retained in the position.[269]

As General Secretary, Stalin had had a free hand in making appointments to his own staff, implanting his loyalists throughout the party and administration.[270] Favouring new Communist Party members, many from worker and peasant backgrounds, to the "Old Bolsheviks" who tended to be university educated,[271] he ensured he had loyalists dispersed across the country's regions.[272] Stalin had much contact with young party functionaries,[273] and the desire for promotion led many provincial figures to seek to impress Stalin and gain his favour.[274] Stalin also developed close relations with the trio at the heart of the secret police (first the Cheka and then its replacement, the State Political Directorate): Felix Dzerzhinsky, Genrikh Yagoda, and Vyacheslav Menzhinsky.[275] In his private life, he divided his time between his Kremlin apartment and a dacha at Zubalova;[276] his wife gave birth to a daughter, Svetlana, in February 1926.[277]

In the wake of Lenin's death, various protagonists emerged in the struggle to become his successor: alongside Stalin was Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, and Mikhail Tomsky.[278] Stalin saw Trotsky—whom he personally despised[279]—as the main obstacle to his dominance within the party.[280] While Lenin had been ill he had forged an anti-Trotsky alliance with Kamenev and Zinoviev.[281] Although Zinoviev was concerned about Stalin's growing authority, he rallied behind him at the 13th Congress as a counterweight to Trotsky, who now led a party faction known as the Left Opposition.[282] The Left Opposition believed the NEP conceded too much to capitalism; Stalin was called a "rightist" for his support of the policy.[283] Stalin built up a retinue of his supporters in the Central Committee,[284] while the Left Opposition were gradually removed from their positions of influence.[285] He was supported in this by Bukharin, who like Stalin believed that the Left Opposition's proposals would plunge the Soviet Union into instability.[286]

In late 1924, Stalin moved against Kamenev and Zinoviev, removing their supporters from key positions.[287] In 1925, Kamenev and Zinoviev moved into open opposition of Stalin and Bukharin.[288] They attacked one another at the 14th Party Congress, where Stalin accused Kamenev and Zinoviev of reintroducing factionalism—and thus instability—into the party.[289] In mid-1926, Kamenev and Zinoviev joined with Trotsky's supporters to form the United Opposition against Stalin;[290]in October they agreed to stop factional activity under threat of expulsion, and later publicly recanted their views under Stalin's command.[291] The factionalist arguments continued, with Stalin threatening to resign in October and then December 1926 and again in December 1927.[292] In October 1927, Zinoviev and Trotsky were removed from the Central Committee;[293] the latter was exiled to Kazakhstan and later deported from the country in 1929.[294] Some of those United Opposition members who were repentant were later rehabilitated and returned to government.[295]

Stalin was now the party's supreme leader,[296] although was not the head of government, a task he entrusted to key ally Vyacheslav Molotov.[297] Other important supporters on the Politburo were Voroshilov, Lazar Kaganovich, and Sergo Ordzhonikidze,[298] with Stalin ensuring his allies ran the various state institutions.[299] According to Montefiore, at this point "Stalin was the leader of the oligarchs but he was far from a dictator".[300]His growing influence was reflected in the naming of various locations after him; in June 1924 the Ukrainian mining town of Yuzovka became Stalino,[301] and in April 1925, Tsaritsyn was renamed Stalingrad on the order of Mikhail Kalinin and Avel Enukidze.[302]

In 1926, Stalin published On Questions of Leninism.[303] Here, he introduced the concept of "Socialism in One Country", which he presented as an orthodox Leninist perspective. It nevertheless clashed with established Bolshevik views that socialism could not be established in one country but could only be achieved globally through the process of world revolution.[303] In 1927, there was some argument in the party over Soviet policy regarding China. Stalin had called for the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong, to ally itself with Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang (KMT) nationalists, viewing a Communist-Kuomintang alliance as the best bulwark against Japanese imperial expansionism. Instead, the KMT repressed the Communists and a civil war broke out between the two sides.[304]

Dekulakisation, collectivisation, and industrialisation: 1927–1931

Economic policy

We have fallen behind the advanced countries by fifty to a hundred years. We must close that gap in ten years. Either we do this or we'll be crushed. This is what our obligations before the workers and peasants of the USSR dictate to us.

— Stalin, February 1931[305]

The Soviet Union lagged behind the industrial development of Western countries,[306] and there had been a shortfall of grain; 1927 produced only 70% of grain produced in 1926.[307] Stalin's government feared attack from Japan, France, the United Kingdom, Poland, and Romania.[308] Many Communists, including in Komsomol, OGPU, and the Red Army, were eager to be rid of the NEP and its market-oriented approach;[309] they had concerns about those who profited from the policy: affluent peasants known as "kulaks" and the small business owners or "Nepmen".[310] At this point, Stalin turned against the NEP, putting him on a course to the "left" even of Trotsky or Zinoviev.[311]

In early 1928 Stalin travelled to Novosibirsk, where he alleged that kulaks were hoarding their grain and ordered that the kulaks be arrested and their grain confiscated, with Stalin bringing much of the area's grain back to Moscow with him in February.[312] At his command, grain procurement squads surfaced across Western Siberia and the Urals, with violence breaking out between these squads and the peasantry.[313] Stalin announced that both kulaks and the "middle peasants" must be coerced into releasing their harvest.[314] Bukharin and several other Central Committee members were angry that they had not been consulted about this measure, which they deemed rash.[315] In January 1930, the Politburo approved the liquidation of the kulak class; accused kulaks were rounded up and exiled to other parts of the country or to concentration camps.[316]Large numbers died during the journey.[317] By July 1930, over 320,000 households had been affected by the de-kulakisation policy.[316]According to Stalin biographer Dmitri Volkogonov, de-kulakisation was "the first mass terror applied by Stalin in his own country".[318]

In 1929, the Politburo announced the mass collectivisation of agriculture,[320]establishing both kolkhozy collective farms and sovkhoz state farms.[321] Stalin barred kulaks from joining these collectives.[322]Although officially voluntary, many peasants joined the collectives out of fear they would face the fate of the kulaks; others joined amid intimidation and violence from party loyalists.[323] By 1932, about 62% of households involved in agriculture were part of collectives, and by 1936 this had risen to 90%.[324] Many of the collectivised peasants resented the loss of their private farmland,[325] and productivity slumped.[326] Famine broke out in many areas,[327] with the Politburo frequently ordering the distribution of emergency food relief to these regions.[328] Armed peasant uprisings against dekulakisation and collectivisation broke out in Ukraine, northern Caucasus, southern Russia, and central Asia, reaching their apex in March 1930; these were suppressed by the Red Army.[329] Stalin responded to the uprisings with an article insisting that collectivisation was voluntary and blaming any violence and other excesses on local officials.[330] Although he and Stalin had been close for many years,[331] Bukharin expressed concerns about these policies; he regarded them as a return to Lenin's old "war communism" policy and believed that it would fail. By mid-1928 he was unable to rally sufficient support in the party to oppose the reforms.[332] In November 1929 Stalin removed him from the Politburo.[333]

Officially, the Soviet Union had replaced the "irrationality" and "wastefulness" of a market economy with a planned economy organised along a long-term, precise, and scientific framework; in reality, Soviet economics were based on ad hoc commandments issued from the centre, often to make short-term targets.[334] In 1928, the first five-year plan was launched, its main focus on boosting heavy industry;[335] it was finished a year ahead of schedule, in 1932.[336] The USSR underwent a massive economic transformation.[337] New mines were opened, new cities like Magnitogorsk constructed, and work on the White Sea-Baltic Canal begun.[337] Millions of peasants moved to the cities, although urban house building could not keep up with the demand.[337] Large debts were accrued purchasing foreign-made machinery.[338] Many of the major construction projects, including the White Sea-Baltic Canal and the Moscow Metro, were constructed largely through forced labour.[339] The last elements of workers' control over industry were removed, with factory managers increasing their authority and receiving privileges and perks;[340] Stalin defended wage disparity by pointing to Marx's argument that it was necessary during the lower stages of socialism.[341] To promote the intensification of labour, a series of medals and awards as well as the Stakhanovite movement were introduced.[319] Stalin's message was that socialism was being established in the USSR while capitalism was crumbling amid the Wall Street crash.[342] His speeches and articles reflected his utopian vision of the Soviet Union rising to unparalleled heights of human development, creating a "new Soviet person". [343]

Cultural and foreign policy

In 1928, Stalin declared that class war between the proletariat and their enemies would intensify as socialism developed.[344] He warned of a "danger from the right", including in the Communist Party itself.[345] The first major show trial in the USSR was the Shakhty Trial of 1928, in which several middle-class "industrial specialists" were convicted of sabotage.[346] From 1929 to 1930, further show trials were held to intimidate opposition:[347] these included the Industrial Party Trial, Menshevik Trial, and Metro-Vickers Trial.[348] Aware that the ethnic Russian majority may have concerns about being ruled by a Georgian,[349] he promoted ethnic Russians throughout the state hierarchy and made the Russian language compulsory throughout schools and offices, albeit to be used in tandem with local languages in areas with non-Russian majorities.[350] Nationalist sentiment among ethnic minorities was suppressed.[351] Conservative social policies were promoted to enhance social discipline and boost population growth; this included a focus on strong family units and motherhood, the re-criminalisation of homosexuality, restrictions placed on abortion and divorce, and the abolition of the Zhenotdel women's department.[352]

Stalin desired a "cultural revolution",[353]entailing both the creation of a culture for the "masses" and the wider dissemination of previously elite culture.[354] He oversaw the proliferation of schools, newspapers, and libraries, as well as the advancement of literacy and numeracy.[355] "Socialist realism" was promoted throughout the arts,[356] while Stalin personally wooed prominent writers, namely Maxim Gorky, Mikhail Sholokhov, and Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy.[357] He also expressed patronage for scientists whose research fitted within his preconceived interpretation of Marxism; he for instance endorsed the research of agrobiologist Trofim Lysenko despite the fact that it was rejected by the majority of Lysenko's scientific peers as pseudo-scientific.[358] The government's anti-religious campaign was re-intensified,[359] with increased funding given to the League of Militant Atheists.[351] Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and Buddhist clergy faced persecution.[347] Many religious buildings were demolished, most notably Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, destroyed in 1931 to make way for the (never completed) Palace of the Soviets.[360] Religion retained an influence over much of the population; in the 1937 census, 57% of respondents identified as religious.[361]

Throughout the 1920s and beyond, Stalin placed a high priority on foreign policy.[362] He personally met with a range of Western visitors, including George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, both of whom were impressed with him.[363] Through the Communist International, Stalin's government exerted a strong influence over Marxist parties elsewhere in the world;[364] initially, Stalin left the running of the organisation largely to Bukharin.[365] At its 6th Congress in July 1928, Stalin informed delegates that the main threat to socialism came not from the right but from non-Marxist socialists and social democrats, whom he called "social fascists";[366]Stalin recognised that in many countries, the social democrats were the Marxist-Leninists' main rivals for working-class support.[367] This preoccupation with opposing rival leftists concerned Bukharin, who regarded the growth of fascism and the far right across Europe as a far greater threat.[365] After Bukharin's departure, Stalin placed the Communist International under the administration of Dmitry Manuilskyand Osip Piatnitsky.[364]

Stalin faced problems in his family life. In 1929, his son Yakov unsuccessfully attempted suicide; his failure earned Stalin's contempt.[368] His relationship with Nadya was also strained amid their arguments and her mental health problems.[369] In November 1932, after a group dinner in the Kremlin in which Stalin flirted with other women, Nadya shot herself.[370] Publicly, the cause of death was given as appendicitis; Stalin also concealed the real cause of death from his children.[371] Stalin's friends noted that he underwent a significant change following her suicide, becoming emotionally harder.[372]

Major crises: 1932–1939

Famine

Within the Soviet Union, there was widespread civic disgruntlement against Stalin's government.[373] Social unrest, previously restricted largely to the countryside, was increasingly evident in urban areas, prompting Stalin to ease on some of his economic policies in 1932.[374]In May 1932, he introduced a system of kolkhoz markets where peasants could trade their surplus produce.[375] At the same time, penal sanctions became more severe; at Stalin's instigation, in August 1932 a decree was introduced meaning that the theft of even a handful of grain could be a capital offense.[376] The second five-year plan had its production quotas reduced from that of the first, with the main emphasis now being on improving living conditions.[374] It therefore emphasised the expansion of housing space and the production of consumer goods.[374] Like its predecessor, this Plan was repeatedly amended to meet changing situations; there was for instance an increasing emphasis placed on armament production after Adolf Hitler became German Chancellor in 1933.[377]

The Soviet Union experienced a major famine which peaked in the winter of 1932–33;[378] between five and seven million people died.[379] Worst affected were Ukraine and the North Caucuses, although the famine also impacted Kazakhstan and several Russian provinces.[380] Historians have long debated whether Stalin's government had intended the famine to occur or not;[381] there are no known documents in which Stalin or his government explicitly called for starvation to be used against the population.[382] The 1931 and 1932 harvests had been poor ones due to weather conditions,[383] and had followed several years in which lower productivity had resulted in a gradual decline in output.[379] Government policies—including the focus on rapid industrialisation, the socialisation of livestock, and the emphasis on sown areas over crop rotation—exacerbated the problem;[384] the state had also failed to build reserve grain stocks for such an emergency.[385] Stalin blamed the famine on hostile elements and wreckers within the peasantry;[386] his government provided small amounts of food to famine-struck rural areas, although this was wholly insufficient to deal with the levels of starvation.[387] In keeping with their ideology, the Communists believed that food supplies should be prioritised for the urban workforce;[388] for Stalin, the fate of Soviet industrialisation was far more important than the lives of the peasantry.[389] Grain exports, which were a major means of Soviet payment for machinery, declined heavily.[387] Stalin would not acknowledge that his policies had contributed to the famine,[376] the existence of which was denied to foreign observers.[390]

Final years: 1950–1953

In his later years, Stalin was in poor health.[630] He took increasingly long holidays; in 1950 and again in 1951 he spent almost five months vacationing at his Abkhazian dacha.[631] Stalin nevertheless mistrusted his doctors; in January 1952 he had one imprisoned after they suggested that he should retire to improve his health.[630] In September 1952, several Kremlin doctors were arrested for allegedly plotting to kill senior politicians in what came to be known as the Doctors' Plot; the majority of the accused were Jewish.[632] He instructed the arrested doctors to be tortured to ensure confession.[633] In November, the Slánský trial took place in Czechoslovakia as 13 senior Communist Party figures, 11 of them Jewish, were accused and convicted of being part of a vast Zionist-American conspiracy to subvert Eastern Bloc governments.[634] That same month, a much publicised trial of accused Jewish industrial wreckers took place in Ukraine.[635] In 1951, he initiated the Mingrelian affair, a purge of the Georgian branch of the Communist Party which resulted in over 11,000 deportations.[636]

From 1946 until his death, Stalin only gave three public speeches, two of which lasted only a few minutes.[637] The amount of written material that he produced also declined.[637] In 1950, Stalin issued the article "Marxism and Problems of Linguistics", which reflected his interest in questions of Russian nationhood.[638] In 1952, Stalin's last book, Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR, was published. It sought to provide a guide to leading the country for after his death.[639] In October 1952, Stalin gave an hour and a half speech at the Central Committee plenum.[640] There, he emphasised what he regarded as leadership qualities necessary in the future and highlighted the weaknesses of various potential successors, particularly Molotov and Mikoyan.[641] In 1952, he also eliminated the Politburo and replaced it with a larger version which he called the Presidium.[642]

Death, funeral and aftermath: 1953

On 1 March 1953, Stalin's staff found him semi-conscious on the bedroom floor of his Volynskoe dacha.[643] He had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage.[644] He was moved onto a couch and remained there for three days.[645]He was hand-fed using a spoon, given various medicines and injections, and leeches were applied to him.[644] Svetlana and Vasily were called to the dacha on 2 March; the latter was drunk and angrily shouted at the doctors, resulting in him being sent home.[646] Stalin died on 5 March 1953.[647] According to Svetlana, it had been "a difficult and terrible death".[648] An autopsy revealed that he had died of a cerebral hemorrhage and that he also suffered from severe damage to his cerebral arteries due to atherosclerosis.[649] It is possible that Stalin was murdered.[650] Beria has been suspected of murder, although no firm evidence has ever appeared.[644]

Stalin's death was announced on 6 March.[651] The body was embalmed,[652] and then placed on display in Moscow's House of Unions for three days.[653] Crowds were such that a crush killed around 100 people.[654]The funeral involved the body being laid to rest in Lenin's Mausoleum in Red Square on 9 March; hundreds of thousands attended.[655] That month featured a surge in arrests for "anti-Soviet agitation" as those celebrating Stalin's death came to police attention.[656] The Chinese government instituted a period of official mourning for Stalin's death.[657]

Stalin left no anointed successor nor a framework within which a transfer of power could take place.[658] The Central Committee met on the day of his death, with Malenkov, Beria, and Khruschev emerging as the party's key figures.[659] The system of collective leadership was restored, and measures introduced to prevent any one member attaining autocratic domination again.[660] The collective leadership included the following eight senior members of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union listed according to the order of precedence presented formally on 5 March 1953: Georgy Malenkov, Lavrentiy Beria, Vyacheslav Molotov, Kliment Voroshilov, Nikita Khrushchev, Nikolai Bulganin, Lazar Kaganovich and Anastas Mikoyan.[661] Reforms to the Soviet system were immediately implemented.[662]Economic reform scaled back the mass construction projects, placed a new emphasis on house building, and eased the levels of taxation on the peasantry to stimulate production.[663] The new leaders sought rapprochement with Yugoslavia and a less hostile relationship with the U.S.,[664] pursuing a negotiated end to the Korean War in July 1953.[665]The doctors who had been imprisoned were released and the anti-Semitic purges ceased.[666] A mass amnesty for those imprisoned for non-political crimes was issued, halving the country's inmate population, while the state security and Gulag systems were reformed, with torture being banned in April 1953.[663]

Personal life and characteristics

Stalin brutally, artfully, indefatigably built a personal dictatorship within the Bolshevik dictatorship. Then he launched and saw through a bloody socialist remaking of the entire former empire, presided over a victory in the greatest war in human history, and took the Soviet Union to the epicentre of global affairs. More than for any other historical figure, even Gandhi or Churchill, a biography of Stalin... eventually comes to approximate a history of the world.

— Stephen Kotkin[709]

Ethnically Georgian,[710] Stalin grew up speaking the Georgian language,[711] and only learned Russian when aged eight or nine.[712] He remained proud of his Georgian identity,[713] and throughout his life retained a Georgian accent when speaking Russian.[714] According to Montefiore, Stalin was profoundly Georgian in his lifestyle and personality;[715] Service noted that Stalin "would never be Russian", could not credibly pass as one, and never tried to pretend he was.[716] Stalin's colleagues described him as "Asiatic", and he told a Japanese journalist that "I am not a European man, but an Asian, a Russified Georgian".[717] Montefiore was of the view that "after 1917, he became quadri-national: Georgian by nationality, Russian by loyalty, internationalist by ideology, Soviet by citizenship."[718]

Stalin had a soft voice,[719] and when speaking Russian did so slowly, carefully choosing his phrasing.[710] In private he used coarse language, although avoided doing so in public.[720] Described as a poor orator,[721]according to Volkogonov, Stalin's speaking style was "simple and clear, without flights of fancy, catchy phrases or platform histrionics".[722] He rarely spoke before large audiences, and preferred to express himself in written form.[723] His writing style was similar, being characterised by its simplicity, clarity, and conciseness.[724] Throughout his life, he used various nicknames and pseudonyms, including "Koba", "Soselo", and "Ivanov",[725] adopting "Stalin" in 1912; it was based on the Russian word for "steel" and has often been translated as "Man of Steel".[146]

In adulthood, Stalin measured 5 feet 4 inches (1.63 m) tall.[726] To appear taller, he wore stacked shoes, and stood on a small platform during parades.[727] His mustached face was pock-marked from smallpox during childhood; this was airbrushed from published photographs.[728] He was born with a webbed left foot, and his left arm had been permanently injured in childhood which left it shorter than his right and lacking in flexibility,[729] which was probably the result of being hit, at the age of 12, by a horse-drawn carriage.[730] During his youth, Stalin cultivated a scruffy appearance in rejection of middle-class aesthetic values.[731] He grew his hair long and often wore a beard; for clothing, he often wore a traditional Georgian chokha or a red satin shirt with a grey coat and red fedora.[732] From mid-1918 until his death he favoured military-style clothing, in particular long black boots, light-coloured collarless tunics, and a gun.[733] He was a lifelong smoker, who smoked both a pipe and cigarettes.[734] He had few material demands and lived plainly, with simple and inexpensive clothing and furniture;[735] his interest was in power rather than wealth.[736]

As Soviet leader, Stalin typically awoke around 11 am,[737] with lunch being served between 3 and 5 pm and dinner no earlier than 9 pm;[738]he then worked late into the evening.[739] He often dined with other Politburo members and their families.[740] As leader, he rarely left Moscow unless to go to one of his dachas;[741] he disliked travel,[742] and refused to travel by plane.[743] His choice of favoured holiday house changed over the years,[744] although he holidayed in southern parts of the USSR every year from 1925 to 1936 and again from 1945 to 1951.[745]Along with other senior figures, he had a dacha at Zubalova, 35km outside Moscow,[746] although ceased using it after Nadya's 1932 suicide.[747]After 1932, he favoured holidays in Abkhazia, being a friend of its leader, Nestor Lakoba.[748] In 1934, his new Kuntsevo Dacha was built; 9km from the Kremlin, it became his primary residence.[749] In 1935 he began using a new dacha provided for him by Lakoba at Novy Afon;[750] in 1936, he had the Kholodnaya Rechka dacha built on the Abkhazian coast, designed by Miron Merzhanov.[751]

Personality

Trotsky and several other Soviet figures promoted the idea that Stalin was a mediocrity.[752] This gained widespread acceptance outside the Soviet Union during his lifetime but was misleading.[753]According to Montefiore, "it is clear from hostile and friendly witnesses alike that Stalin was always exceptional, even from childhood".[753] Stalin had a complex mind,[754] great self-control,[755] and an excellent memory.[756] He was a hard worker,[757] and displayed a keen desire to learn;[758] when in power, he scrutinised many details of Soviet life, from film scripts to architectural plans and military hardware.[759] According to Volkogonov, "Stalin's private life and working life were one and the same"; he did not take days off from political activities.[760]

Stalin could play different roles to different audiences,[761] and was adept at deception, often deceiving others as to his true motives and aims.[762]Several historians have seen it appropriate to follow Lazar Kaganovich's description of there being "several Stalins" as a means of understanding his multi-faceted personality.[763] He was a good organiser,[764] with a strategic mind,[765] and judged others according to their inner strength, practicality, and cleverness.[766] He acknowledged that he could be rude and insulting,[767] although rarely raised his voice in anger;[768] as his health deteriorated in later life he became increasingly unpredictable and bad tempered.[769] Despite his tough-talking attitude, he could be very charming;[770] when relaxed, he cracked jokes and mimicked others.[758]Montefiore suggested that this charm was "the foundation of Stalin's power in the Party".[771]

Stalin was ruthless,[772] temperamentally cruel,[773] and had a propensity for violence high even among the Bolsheviks.[768] He lacked compassion,[774] something Volkogonov suggested might have been accentuated by his many years in prison and exile,[775] although he was capable of acts of kindness to strangers, even amid the Great Terror.[776] He was capable of self-righteous indignation,[777] and was resentful,[778] vindictive,[779] and vengeful, holding onto grievances against others for many years.[780] By the 1920s, he was also suspicious and conspiratorial, prone to believing that people were plotting against him and that there were vast international conspiracies behind acts of dissent.[781] He never attended torture sessions or executions,[782] although Service thought Stalin "derived deep satisfaction" from degrading and humiliating people and keeping even close associates in a state of "unrelieved fear".[708]Montefiore thought Stalin's brutality marked him out as a "natural extremist";[783] Service suggested he had a paranoid or sociopathic personality disorder.[754] Other historians linked his brutality not to any personality trait, but to his unwavering commitment to the survival of the Soviet Union and the international Marxist-Leninist cause.[784]

It is hard for me to reconcile the courtesy and consideration he showed me personally with the ghastly cruelty of his wholesale liquidations. Others, who did not know him personally, see only the tyrant in Stalin. I saw the other side as well – his high intelligence, that fantastic grasp of detail, his shrewdness and his surprising human sensitivity that he was capable of showing, at least in the war years. I found him better informed than Roosevelt, more realistic than Churchill, in some ways the most effective of the war leaders... I must confess that for me Stalin remains the most inscrutable and contradictory character I have known – and leave the final word to the judgment of history.

— U.S. ambassador W. Averell Harriman[785]

Keenly interested in the arts,[786] Stalin admired artistic talent.[787] He protected several Soviet writers, such as Mikhail Bulgakov, even when their work was labelled harmful to his regime.[788] He enjoyed music,[789]owning around 2,700 albums,[790] and frequently attending the Bolshoi Theatre during the 1930s and 1940s.[791] His taste in music and theatre was conservative, favouring classical drama, opera, and ballet over what he dismissed as experimental "formalism".[712] He also favoured classical forms in the visual arts, disliking avant-garde styles like cubism and futurism.[792] He was a voracious reader, with a library of over 20,000 books.[793] Little of this was fiction,[794] although he could cite passages from Alexander Pushkin, Nikolay Nekrasov, and Walt Whitman by heart.[787] He favoured historical studies, keeping up with debates in the study of Russian, Mesopotamian, ancient Roman, and Byzantine history.[637] An autodidact,[795] he claimed to read as many as 500 pages a day,[796] with Montefiore regarding him as an intellectual.[797] Stalin also enjoyed watching films late at night at cinemas installed in the Kremlin and his dachas.[798] He favoured the Western genre;[799] his favourite film was the 1938 picture Volga Volga.[800]

Stalin was a keen and accomplished billiards player,[801] and collected watches.[802] He also enjoyed practical jokes; he for instance would place a tomato on the seat of Politburo members and wait for them to sit on it.[803] When at social events, he encouraged singing,[804] as well as alcohol consumption; he hoped that others would drunkenly reveal their secrets to him.[805] As an infant, Stalin displayed a love of flowers,[806]and later in life he became a keen gardener.[806] His Volynskoe suburb had a 50-acre park, with Stalin devoting much attention to its agricultural activities.[807]

Stalin publicly condemned anti-Semitism,[808] although was repeatedly accused of it.[809] People who knew him, such as Khrushchev, suggested he long harbored negative sentiments toward Jews,[810] and anti-Semitic trends in his policies were further fueled by Stalin's struggle against Trotsky.[811] After Stalin's death, Khrushchev claimed that Stalin encouraged him to incite anti-Semitism in Ukraine, allegedly telling him that "the good workers at the factory should be given clubs so they can beat the hell out of those Jews."[812] In 1946, Stalin allegedly said privately that "every Jew is a potential spy."[813] Conquest stated that although Stalin had Jewish associates, he promoted anti-Semitism.[814] Service cautioned that there was "no irrefutable evidence" of anti-Semitism in Stalin's published work, although his private statements and public actions were "undeniably reminiscent of crude antagonism towards Jews";[815] he added that throughout Stalin's lifetime, the Georgian "would be the friend, associate or leader of countless individual Jews".[816]According to Beria, Stalin had affairs with several Jewish women.[817]

Relationships and family

Stalin carrying his daughter, Svetlana

Stalin carrying his daughter, Svetlana

Friendship was important to Stalin,[818]and he used it to gain and maintain power.[819] Kotkin observed that Stalin "generally gravitated to people like himself: parvenu intelligentsia of humble background".[820]He gave nicknames to his favourites, for instance referring to Yezhov as "my blackberry".[821] Stalin was sociable and enjoyed a joke.[822] According to Montefiore, Stalin's friendships "meandered between love, admiration, and venomous jealousy".[823]While head of the Soviet Union he remained in contact with many of his old friends in Georgia, sending them letters and gifts of money.[824]

Stalin was attracted to women and there are no reports of any homosexual tendencies;[825] according to Montefiore, in his early life Stalin "rarely seems to have been without a girlfriend".[50] He was sexually promiscuous, although rarely talked about his sex life.[826] Montefiore noted that Stalin's favoured types were "young, malleable teenagers or buxom peasant women",[826] who would be supportive and unchallenging toward him.[827] According to Service, Stalin "regarded women as a resource for sexual gratification and domestic comfort".[828]Stalin married twice and had several offspring.[825] He married his first wife, Ekaterina Svanidze, in 1906. According to Montefiore, theirs was "a true love match";[829] Volkogonov suggested that she was "probably the one human being he had really loved".[830] They had a son, Yakov, who often frustrated and annoyed Stalin.[831] Yakov had a daughter, Galina, before fighting for the Red Army in the Second World War. He was captured by the German Army and then committed suicide.[832]

Stalin's second wife was Nadezhda Alliluyeva; theirs was not an easy relationship, and they often rowed.[833] They had two biological children—a son, Vasily, and a daughter, Svetlana—and adopted another son, Artyom Sergeev, in 1921.[834] During his marriage to Nadezhda, Stalin had affairs with many other women, most of whom were fellow revolutionaries or their wives.[835] Nadezdha suspected that this was the case,[836] and committed suicide in 1932.[837] Stalin regarded Vasily as spoiled and often chastised his behaviour; as Stalin's son, Vasily nevertheless was swiftly promoted through the ranks of the Red Army and allowed a lavish lifestyle.[838] Conversely, Stalin had an affectionate relationship with Svetlana during her childhood,[839] and was also very fond of Artyom.[834] In later life, he disapproved of Svetlana's various suitors and husbands, putting a strain on his relationship with her.[840] After the Second World War he made little time for his children and his family played a decreasingly important role in his life.[841] After Stalin's death, Svetlana changed her surname from Stalin to Allilueva,[664] and defected to the U.S.[842]

After Nadezdha's death, Stalin became increasingly close to his sister-in-law Zhenya Alliluyeva;[843] Montefiore believed that they were probably lovers.[844] There are unproven rumours that from 1934 onward he had a relationship with his housekeeper Valentina Istomina.[845] Stalin had at least two illegitimate children,[846] although he never recognised these as being his.[847] One of these, Constantin Kuzakova, later taught philosophy at the Leningrad Military Mechanical Institute, but never met his father.[848] The other, Alexander, was the son of Lidia Pereprygia; he was raised as the son of a peasant fisherman and the Soviet authorities made him swear never to reveal that Stalin was his biological father.[849]

Legacy

The historian Robert Conquest stated that Stalin, "perhaps[…] determined the course of the twentieth century" more than anyone other individual.[850] Biographers like Service and Volkogonov have considered him an outstanding and exceptional politician;[851] Montefiore labelled Stalin as "that rare combination: both 'intellectual' and killer", a man who was "the ultimate politician" and "the most elusive and fascinating of the twentieth-century titans".[852] According to historian Kevin McDermott, interpretations of Stalin range from "the sycophantic and adulatory to the vitriolic and condemnatory".[853] For most Westerners and anti-communist Russians, he is viewed overwhelmingly negatively as a mass murderer;[853] for significant numbers of Russians and Georgians, he is regarded as a great statesman and state-builder.[853]

Stalin strengthened and stabilised the Soviet Union;[854] Service suggested that without him the country might have collapsed long before 1991.[854] In under three decades, Stalin transformed the Soviet Union into a major industrial world power,[855] one which could "claim impressive achievements" in terms of urbanisation, military strength, education, and Soviet pride.[856] Under his rule, the average Soviet life expectancy grew due to improved living conditions, nutrition, and medical care;[857]mortality rates declined.[858] Although millions of Soviet citizens despised him, support for Stalin was nevertheless widespread throughout Soviet society.[856]

Stalin's Soviet Union has been characterised as a totalitarian state,[859]with Stalin its authoritarian leader.[860] Various biographers have described him as a dictator,[861] an autocrat,[862] or accused him of practicing Caesarism.[863] Montefiore argued that while Stalin initially ruled as part of a Communist Party oligarchy, in 1934 the Soviet government transformed from this oligarchy into a personal dictatorship,[864] with Stalin only becoming "absolute dictator" between March and June 1937, when senior military and NKVD figures were eliminated.[865]According to Kotkin, Stalin "built a personal dictatorship within the Bolshevik dictatorship".[709] In both the Soviet Union and elsewhere he came to be portrayed as an "Oriental despot".[866] The biographer Dmitri Volkogonov characterised him as "one of the most powerful figures in human history",[867] while McDermott stated that Stalin had "concentrated unprecedented political authority in his hands",[868] and Service noted that by the late 1930s, Stalin "had come closer to personal despotism than almost any monarch in history".[869] According to historian James Harris, contemporary archival research shows that the motivation behind the purges was not Stalin attempting to establish his own personal dictatorship; evidence suggests he was committed to building the socialist state envisioned by Lenin. The real motivation for the terror, according to Harris, was an over-exaggerated fear of counterrevolution.[870]

McDermott nevertheless cautioned against "over-simplistic stereotypes"—promoted in the fiction of writers like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Vasily Grossman, and Anatoly Rybakov—that portrayed Stalin as an omnipotent and omnipresent tyrant who controlled every aspect of Soviet life through repression and totalitarianism.[871] Service similarly warned of the portrayal of Stalin as an "unimpeded despot", noting that "powerful though he was, his powers were not limitless", and his rule depended on his willingness to conserve the Soviet structure he had inherited.[872] Kotkin observed that Stalin's ability to remain in power relied on him having a majority in the Politburo at all times.[873] Khlevniuk noted that at various points, particularly when Stalin was old and frail, there were "periodic manifestations" in which the party oligarchy threatened his autocratic control.[769] Stalin denied to foreign visitors that he was a dictator, stating that those who labelled him such did not understand the Soviet governance structure.[874]